Teacher practice is more than meets the eye. If we focus only on what's easy to observe, we'll miss the heart of teaching—professional judgment.

By Justin Baeder, PhD

90% Hidden Beneath the Surface

Like an iceberg, most of teacher practice lies beneath the surface, where it's difficult to observe directly.

While it certainly matters how teachers facilitate activities, explain concepts, and manage the classroom, much of their success comes from what they've already done before the lesson.

A teacher who has established expectations, developed deep content and pedagogical knowledge, planned a quality lesson, and built relationships with students and families will get dramatically different results from a teacher who does all the same things in class, but hasn't done the deeper work.

Yet many instructional leadership efforts treat what's readily visible as if it's all that exists.

At The Principal Center, we call this tendency observability bias:

Observability bias is the tendency of instructional leaders to focus on what is easiest for them to observe, rather than the key decisions teachers are making.

Observability bias leads observers to mistake what they can see for the entirety of practice.

Just as a facade is not the same as an actual house, observable look-fors aren’t the same as the actual practice educators are enacting.

—Mapping Professional Practice: How to Develop Instructional Frameworks to Support Teacher Growth, by Heather Bell-Williams & Justin Baeder, p. 18. © 2022 Solution Tree

Instructional leaders can fall into the observability bias trap when conducting the two primary teacher supervision and evaluation activities:

For example, an observation or walkthrough form must, by its very nature, focus on features that are easy to observe, such as:

- Whether students are on task

- Whether the learning target and success criteria are posted on the wall

- Whether the teacher is using a particular instructional technique

Yet visible teaching behaviors are just a small fraction of what matters.

To get a more complete picture and see the whole “iceberg” of practice, we can look to maps like Charlotte Danielson's Framework for Teaching.

Danielson's 4 Domains of Teacher Practice

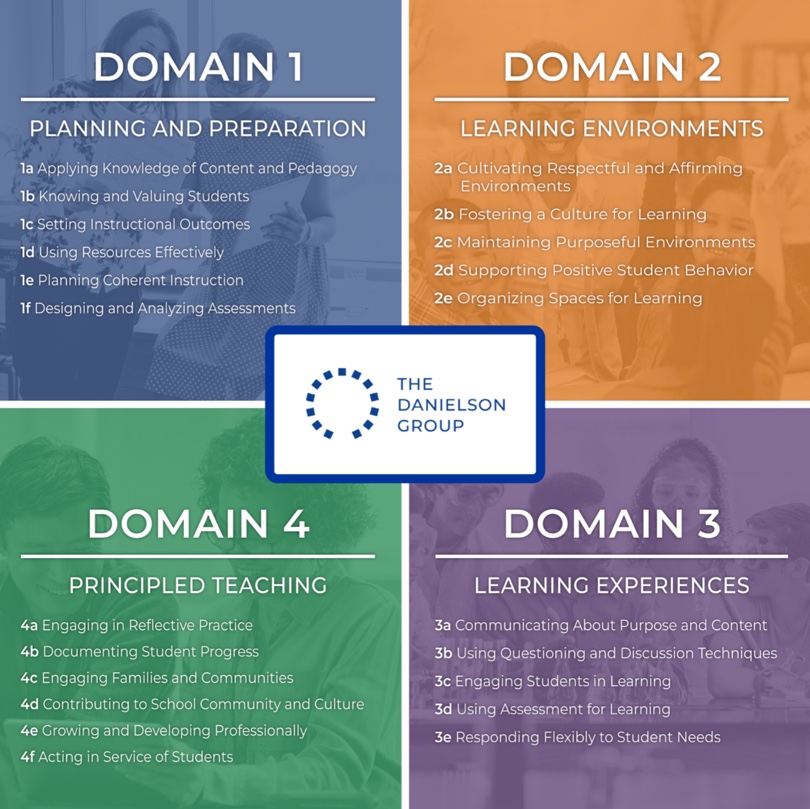

In the latest iteration of her Framework for Teaching, Charlotte Danielson identifies four major domains of teacher practice:

- Planning and Preparation

- Learning Environments

- Learning Experiences

- Principled Teaching

Notably, only the Learning Environments and Learning Experiences domains address what actually happens during class time—only some of which is directly observable.

Fortunately, many teacher evaluation systems are based on all four of Danielson's domains, so—in theory, at least—administrators are obliged to consider the work teachers do outside of class time to ensure student success.

But how can we gather evidence of teacher practice we can't observe?

Gathering Evidence of the Invisible

Gathering insight into areas of practice that are hard to observe directly requires us to rethink our approach to evidence.

Perhaps the first step is to abandon the hubris that leads us to assume “If I can't see it, it doesn't exist.”

Even the most diligent observer sees only a few of the 1,000 hours each teacher spends with students in a given year (though leaders who conduct regular classroom walkthroughs see far more than average).

We miss a great deal of context simply because we can't be there all the time.

But we also miss a great deal because it's not inherently observable—either it happens outside of class time, or it happens entirely inside the teacher's mind.

To get a better sense of teachers' thinking and planning, many administrators ask for lesson plans—perhaps on a regular basis, or perhaps just when observing.

But even the most detailed lesson plans don't capture what really matters: teacher thinking.

Lesson plans, like direct observations, reveal just the surface features of teachers' planning and preparation, so a “checklist” approach to looking at lesson plans will provide fairly little insight.

For example, a lesson plan may contain learning targets, success criteria, and differentiated learning activities.

But what does that really tell us about the teacher's professional judgment? Lesson plans pulled straight from the teacher's guide—or the internet—can check all the right boxes.

What we're really interested in—or should be—is teacher thinking.

And there's only one way to gain direct insight into teacher thinking: conversation.

Conversation: Our Window On Teacher Thinking

Conversation is like a glass-bottomed boat: it allows us to peer beneath the surface and see what's normally hidden from our view.

Talking with teachers gives us a window on their thinking and professional judgment, in a way that no amount of observing or reviewing lesson plans can.

Two priorities can help instructional leaders avoid common pitfalls in feedback conversations:

- Ask good evidence-driven questions

- Let the teacher do most of the talking

If we stray too far into philosophizing or advice-giving, we'll miss the opportunity to hear teachers put their own thinking into words.

Letting the teacher do most of the talking is hard for administrators who have been trained to give a “feedback sandwich” consisting of:

- Compliments

- Suggestions

- Compliments

This type of feedback has little impact on teacher practice, because it's limited by the evidence we're able to gather through direct observation—which, as we've seen, is only a small fraction of the whole “iceberg.”

To avoid the feedback sandwich, try asking open-ended, evidence-driven questions like these:

- Context: I noticed that you [ ]…could you talk to me about how that fits within this lesson or unit?

- Perception: Here’s what I saw students [ ]…what were you thinking was happening at that time?

- Interpretation: At one point in the lesson, it seemed like [ ]… What was your take?

- Decision: Tell me about when you [ ]… What went into that choice?

You can find the full list of 10 evidence-driven feedback questions in Now We're Talking! 21 Days to High-Performance Instructional Leadership.

By getting teachers talking about their practice, we can gain insight into and influence what really matters: their professional judgment.

Professional Judgment, Not Observable Behavior

Ultimately, our impact as instructional leaders doesn't come from giving compliments, suggestions, or tips.

It doesn't come from second-guessing teachers' choices or telling them what's missing on a checklist or form.

If we want to improve teacher practice, we must focus squarely on teacher thinking and professional judgment. We may be able to influence this thinking through our conversation, or we may gain insight into the training, coaching, and resources that would help teachers take their thinking to the next level.

Too often, we give feedback without even taking a moment to explore the thinking behind the observable behavior.

Documenting what we see is important, but it doesn't reveal the whole iceberg of practice—not without conversation.

But how can we use what we do see to keep our conversations evidence-driven, while gaining insight into the unseen domains of practice?

Evidence As A Landing Pad

In a feedback conversation, evidence is our starting point. We share what we see, ask an open-ended question, and let the teacher run with it.

Sometimes it even works better to ask a broken question, and just trail off: “I noticed [ ]. What did you…”

Asking a specific question can be less productive than sharing specific evidence, and letting the teacher choose what to say about it.

This choice reveals what we care about most: professional judgment.

We start with evidence—the visible tip of the iceberg—and let the conversation take us into the depths of teacher practice.

Get Into Classrooms—The Right Way

In Now We're Talking! 21 Days to High-Performance Instructional Leadership, you'll find a model for instructional leadership that gets teachers talking, gives you the insight you need to improve practice, and avoids the pitfalls of observability bias.

When you conduct walkthroughs that have these 7 features, you'll find them rewarding, impactful, and sustainable:

- Frequent—18 biweekly visits per teacher per year

- Brief—around five to fifteen minutes

- Substantive—more than just making an appearance

- Open-ended—focused on the teacher’s instructional decision-making, not just narrow data collection

- Evidence-based—centered on what actually happens in the classroom

- Criterion-referenced—linked to a shared set of expectations

- Conversation-oriented—designed to lead to rich conversations between teachers and instructional leaders

You can get a copy of Now We're Talking by signing up for the Instructional Leadership Challenge, which has helped more than 10,000 leaders in 50+ countries:

- Confidently get into classrooms every day

- Have feedback conversations that change teacher practice

- Discover their best opportunities for school improvement

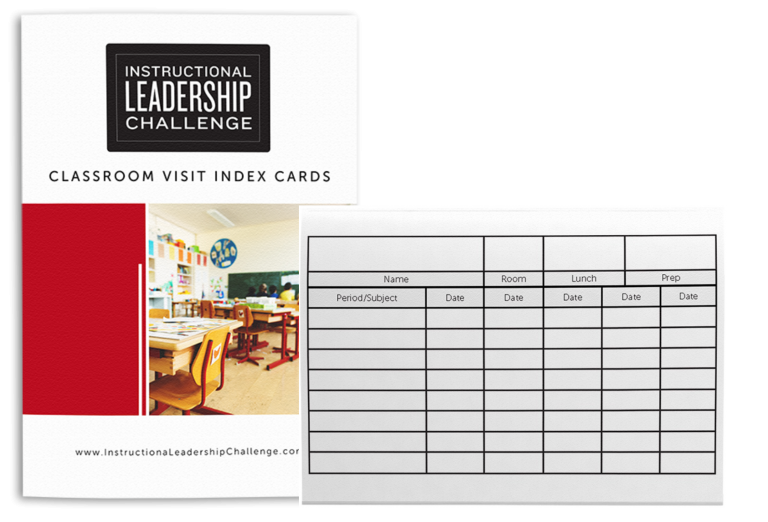

If you'd like to get started right away, you can also download our Classroom Visit Notecards template, so it's easy to find a time to visit each teacher, and easy to keep track of your visits.

About the Author

Justin Baeder, PhD is Director of The Principal Center, where he helps senior leaders in K-12 organizations build capacity for instructional leadership by helping school leaders:

- Confidently get into classrooms every day

- Have feedback conversations that change teacher practice

- Discover their best opportunities for student learning

He holds a PhD in Educational Leadership & Policy from the University of Washington, and is the host of Principal Center Radio, where he interviews education thought leaders.

His book Now We're Talking! 21 Days to High-Performance Instructional Leadership (Solution Tree) is the definitive guide to classroom walkthroughs, and his book Mapping Professional Practice: How to Develop Instructional Frameworks to Support Teacher Growth, with Heather Bell-Williams, helps educators focus on the heart of teacher practice.