Low-inference notes are the foundation of evidence-driven teacher evaluation.

Here's how to capture what you need during observations.

by Justin Baeder, PhD

Why Low-Inference Notes Are Best

“Low-inference” notes have long been the preferred way to document teacher practice in formal observations.

Rather than mix documentation and commentary, low-inference notes push us to defer judgment and continue taking in what's happening around us.

A few tips for taking useful notes:

- Capture verbatim quotes from the teacher and students

- Note each instructional activity and transition

- Include timestamps in your notes, so you can reconstruct the flow of the lesson

- Note what students who aren't talking or getting the teacher's attention are doing, too

- Jot down clarifying questions to ask in the post-conference

The better your notes, the more sound your judgments can be when you ultimately make them.

Why is this such an effective approach?

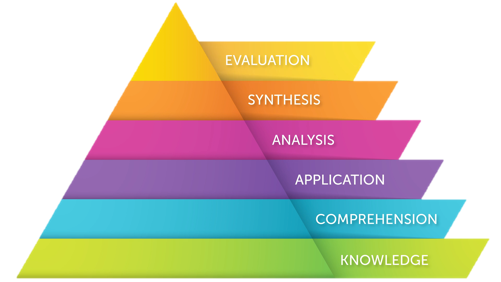

If our goal is ultimately to evaluate, we need to start at the foundation of Bloom's Taxonomy and work our way up:

Skilled observation is a cognitively demanding process. As we take in new information, we're constantly making meaning, noticing connections, and deciding what to focus on next.

We can't stay strictly at the bottom of Bloom's Taxonomy and focus only on knowledge; our ability to make sense of what we're seeing is what makes us better than, say, a video camera.

But the top of the pyramid is a bit of a danger zone. While it's inevitable that we'll strive to make sense of what we're seeing by analyzing, synthesizing, and evaluating as we observe, we simply don't have all of the information we need until we talk with the teacher.

Teacher practice is like an iceberg—what we see above the surface is only about 10% of what's really there.

The remainder is the teacher's invisible thinking, preparation, past instruction, relationships, professional knowledge, and more. We can't truly evaluate teacher practice without any insight into this non-observable 90%.

That's why it's so powerful to write down any clarifying questions to ask the teacher after the observation.

If we jump straight to evaluation—snap judgments based on instant impressions—we're violating the “Hippocratic Oath” for instructional leaders.

The Hippocratic Oath for Instructional Leaders

Working our way up Bloom's Taxonomy helps us ensure that our judgments are based on a solid foundation of knowledge and understanding.

Here's what I call the “Hippocratic Oath for Instructional Leaders:”

The Hippocratic Oath for Instructional Leaders: Seek first to understand, then to be understood.

(You might recognize this as Stephen Covey's 5th Habit of the 7 Habits of Highly Effective People.)

Without a foundation of evidence, our top-of-the-pyramid judgments would be—literally—baseless.

So when we're conducting formal observations, it's essential to take thorough, low-inference notes.

We can use higher-order thinking to determine what matters and direct our attention, but must continually return to capturing factual evidence, and defer judgment until the post-conference.

Can We Really Defer Judgment?

The more objective and low-inference your notes, the more sound your judgments can be when you ultimately make them.

Now, having said all that, I think deferring judgment is something of a myth.

We should strive for it, in the name of intellectual honesty and curiosity.

But judgment is such an integral part of our thinking that we can't just shut it off.

If we could, would our observations be better?

What if you recorded a video of a lesson, had it transcribed, and had ChatGPT write a summary?

I don't think that would be nearly as good as an experienced human observer.

Why?

Because the main way we use our professional judgment while observing and taking low-inference notes is in deciding what to pay attention to.

Using Professional Judgment to Focus Your Attention

Your judgment helps you decide what matters and is worth writing down.

A camera records whatever you point it at, but classrooms are complex, dynamic places.

It takes your full capacity and professional judgment as an instructional leader to decide where to direct your focus.

So don't try to turn off your judgment—direct your cognitive energy toward deciding what matters, and document it as factually as you can.

(By the way, this is why I'm not a fan of forms—because they decide what you should document in advance, without regard for what's happening in the lesson and what's most relevant.)

The Importance of Pre- & Post-Conferences: Feedback As Conversation

To truly understand a lesson, it's essential to talk with the teacher, not just observe.

To see the whole “iceberg” of practice, we need both direct observation and sense-making conversation.

The time-tested practice of meeting with the teacher for pre- and post-observation conferences is designed to:

- Give you an overview of the lesson, including its objectives and main learning activities

- Let the teacher situate the lesson within the larger unit of instruction

- Reveal the teacher's thinking and instructional decision-making, which may not be evident from observation alone

- Prevent you from giving irrelevant feedback (e.g. suggesting an activity that has already been done)

Whether or not these pre- and post-observation meetings are required in your organization, it's essential to make time to talk with the teacher to get perspective on the thinking and decision-making that you can't observe directly.

The Relevance Problem: What's Worth Documenting?

The challenge of taking low-inference notes is relevance—it's easy to document things that don't really matter, and miss things that do.

Perhaps two students were whispering to one another while the teacher was giving directions. Is that worth writing down? It's a judgment call.

Paying attention is a higher-order task, even when it's directed at low-inference description.

A video camera can capture evidence without regard to relevance—and with enough cameras, we could perfectly record every observable element of the lesson, from the work on each student's desk to the expressions on their faces.

But simply capturing more evidence just kicks the can down the road—we'll still have to decide what matters, and there's not enough time in the day to review multiple camera angles.

The best time to decide what's relevant—and therefore worth documenting—is in the moment, while observing.

There's no substitute for a skilled observer taking low-inference notes based on their real-time intuitions about what matters most.

But how can we decide what's relevant? Is it just a matter of personal opinion?

The answer is right in front of us: our teacher evaluation criteria.

Keep Evaluation Criteria In Mind As You Observe

Our teacher evaluation criteria serve as the legal, contractual, and professional basis for teacher evaluation decisions.

If we're ultimately going to use these criteria for our final ratings, why not use them to guide our attention as we observe?

The precise language of our evaluation criteria can give us a vastly more detailed and nuanced lens for observing, so we can take low-inference notes that capture relevant evidence.

For example, we might have an intuitive sense of what a well-planned lesson looks like.

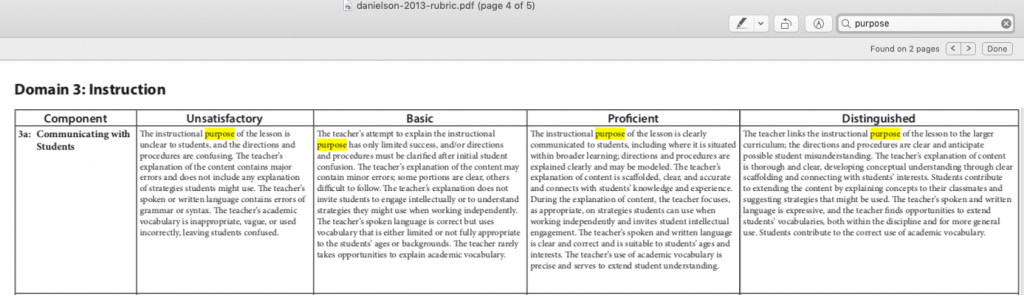

But our evaluation criteria—like Charlotte Danielson's Domain 1, Planning and Preparation, Component e, Designing Coherent Instruction, can help us get far more specific:

Proficient: Most of the learning activities are aligned with the instructional outcomes and follow an organized progression suitable to groups of students. The learning activities have reasonable time allocations; they represent significant cognitive challenge, with some differentiation for different groups of students and varied use of instructional groups.

© 2013 The Danielson Group. All Rights Reserved.

Such detailed expectations draw our attention to facets of practice we might otherwise miss—for example, differentiation or variety in instructional groups.

However, the sheer amount of detail in our evaluation criteria creates a second relevance problem: just as it's hard to decide what evidence is worth capturing in a dynamic classroom, it's hard to decide which criteria to focus on.

Your teacher evaluation rubric may have dozens of criteria—Danielson has around 22, while Marzano has closer to 67—far more than we can keep in mind at once.

The answer to this relevance question is, again, professional judgment. A skilled observer must decide which criteria are most relevant to what's taking place in the classroom.

Bloom's Taxonomy again suggests the importance of knowledge—we must be aware of our evaluation criteria, and comprehend them well enough to do the higher-order work of applying them to the practice we're observing.

This comes with experience, and is aided by the organization of the criteria, e.g. into domains and components like Danielson's. It's reasonably easy to decide whether to focus on planning, classroom management, or instruction, then zoom in on specific criteria.

I'm partial to the 2013 version of the Danielson Framework that shows each domain on one page, each with five to six components, divided into four levels of proficiency—Unsatisfactory, Basic, Proficient, and Distinguished.

But even in its most compact form—and Danielson is one of the more concise frameworks—it's four solid pages of tiny text.

We've all scrolled through long electronic documents or fumbled with paper packets in search of relevant criteria.

How can we quickly find and focus on the most relevant criteria without getting overwhelmed?

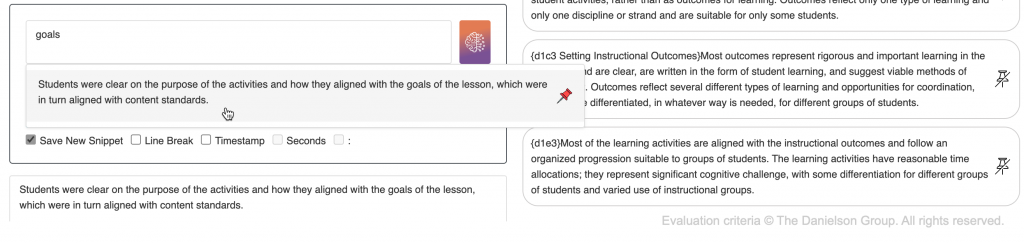

On a recent call with a Repertoire user, I had an idea: what if you could “pin” relevant criteria on the screen as you take notes?

A few days later, our 📌Pinned Snippets✂️ feature went live. Here's how it works, and how you can do something similar if you don't have access to Repertoire.

Find & “Pin” Precise Professional Language with Repertoire or Electronic Documents

As part of our standard setup process, we import each user's evaluation criteria as searchable snippets.

For example, if you type the word “purpose” in the Snippet box, any criteria containing that word will be suggested.

Simply click the red pushpin icon 📌 to pin the snippet in the right column. You can pin as many snippets as you want, and unpin or drag and drop to rearrange them as needed.

If you aren't using Repertoire, you can do a keyword search in the document containing your evaluation criteria:

If you find that this doesn't work, you may be using a scanned document that contains images rather than text. Chances are good that a version with actual text can be easily found online or obtained from your organization.

Looking at your evaluation criteria while observing has several benefits:

- It reminds you of details you might otherwise forget

- It helps you see connections between criteria

- It makes it easier to use specific terms from the criteria in your documentation

The more you take notes with your evaluation criteria in mind, the richer your evidence will be for making evaluation decisions aligned with the criteria.

What else can we do to take more effective low-inference notes?

Capturing the 4th dimension—time—is a great way to take better notes. In the past, it was yet one more thing to worry about while observing, but today, technology now makes it easy to add timestamps.

Use Timestamps to Reconstruct the Flow of the Lesson

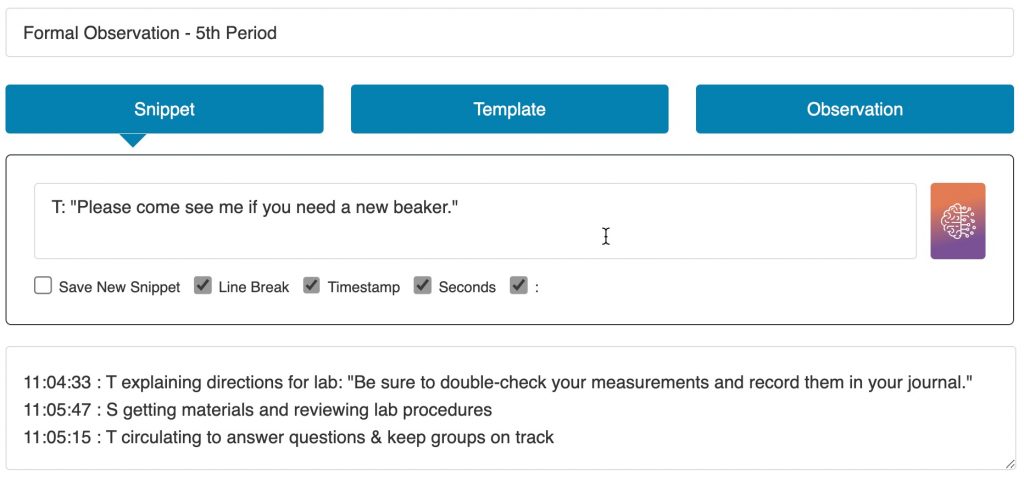

Timestamps are to-the-minute—or even to-the-second—labels accompanying each line of text, usually inserted automatically by software such as Repertoire or TextExpander.

By timestamping each quote or description of what's taking place in the classroom, you can automatically create a record of the chronology of the lesson—what took place, in what order, and how long everything took.

This can make it easy to identify opportunities to save time or otherwise adjust pacing.

For example, if you capture a quote in which students state that they've finished their work, then a later quote in which the teacher transitions the class to the next activity, timestamps will allow you to discuss the pacing of the lesson, without having to explicitly note it as you observe.

What questions should you ask in a post-conference, as you seek to better understand the lesson and the teacher's thinking? I recommend a format that combines specific evidence with an open-ended question.

Ask Evidence-Driven Questions

There are two important priorities for the questions you ask in feedback conversations:

- Focus on specific evidence

- Get the teacher talking

Rather than ask leading questions like “Have you thought about…?” it works best to ask open-ended questions that get the teacher talking, but that start with specific evidence from your visit.

Here are 10 questions you can use—simply share [something you noticed] when you see [ ]:

- Context: I noticed that you [ ]…could you talk to me about how that fits within this lesson or unit?

- Perception: Here’s what I saw students [ ]…what were you thinking was happening at that time?

- Interpretation: At one point in the lesson, it seemed like [ ]… What was your take?

- Decision: Tell me about when you [ ]… What went into that choice?

- Comparison: I noticed that students [ ]… How did that compare with what you had expected to happen when you planned the lesson?

- Antecedent: I noticed that [ ]… Could you tell me about what led up to that, perhaps in an earlier lesson?

- Adjustment: I saw that [ ]… What did you think of that, and what do you plan to do tomorrow?

- Intuition: I noticed that [ ]… How did you feel about how that went?

- Alignment: I noticed that [ ]… What links do you see to our instructional framework?

- Impact: What effect did you think it had when you [ ]?

Download as a PDF: 10 Questions for Better Feedback on Teaching »

Learn More: Evidence-Driven Teacher Evaluation

Want to develop your capacity for instructional leadership through teacher observations and evaluations?

Learn more about the Evidence-Driven Teacher Evaluation Certification Program.

About the Author

Justin Baeder, PhD is Director of The Principal Center, where he helps senior leaders in K-12 organizations build capacity for instructional leadership by helping school leaders:

- Confidently get into classrooms every day

- Have feedback conversations that change teacher practice

- Discover their best opportunities for student learning

He holds a PhD in Educational Leadership & Policy from the University of Washington, and is the host of Principal Center Radio, where he interviews education thought leaders.

His book Now We're Talking! 21 Days to High-Performance Instructional Leadership (Solution Tree) is the definitive guide to classroom walkthroughs, and his book Mapping Professional Practice (with Heather Bell-Williams) helps instructional leaders create instructional frameworks to establish shared expectations for practice.