Progressive discipline is the hidden infrastructure that allows people to co-exist in organizations by setting boundaries for acceptable behavior. Here's what happens when it breaks down—and how to fix it.

By Justin Baeder, PhD

Lately, it seems like the world has gone crazy. Behaviors that were once rare are increasingly commonplace.

In schools, this means an increase in unacceptable behaviors, such as:

- Yelling and screaming

- Profanity and disrespect

- Threats and violence

These behaviors seem to be on the rise among our three main stakeholder groups—students, parents, and staff—and in some cases, even among our fellow administrators and central office staff.

How can we respond when people disrupt the learning environment by behaving in inappropriate ways?

By using the time-tested logic and processes of progressive discipline.

In this article, we'll explore what progressive discipline is, what it means for student discipline, and how it applies to parent and employee misconduct.

What Is Progressive Discipline? Who Is It For?

Progressive discipline, in its original sense, has nothing to do with progressivism or school discipline.

Rather, the term refers to a long-established set of HR practices with escalating (progressive) sanctions (discipline) for repeated misconduct.

You may have seen a few loose references to progressive discipline on The Office, like when Ryan issues Jim a “formal warning” about his performance, and when Dwight rolls out a demerit system, prompting Jim to threaten him with a “full disadulation.”

While the characters on The Office of course hilariously miss the point, progressive discipline is intended to solve two opposing problems:

- Progressive discipline protects the individual against excessive or arbitrary consequences, especially over minor issues.

- Progressive discipline protects the organization against chronic and severe behaviors that disrupt the organization's pursuit of its mission.

In the context of student behavior, progressive discipline makes it possible to respond appropriately to one-time and repeated behaviors, in order to minimize the impact on the school environment, without unfairly harsh punishments.

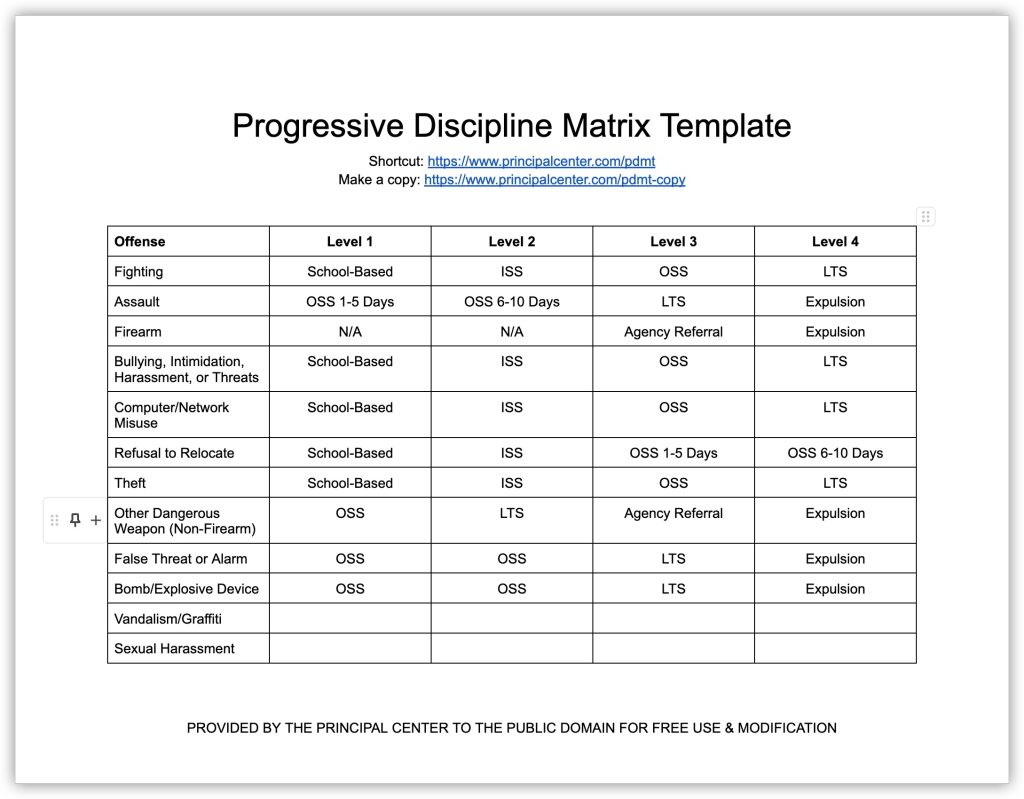

Here's a sample progressive discipline matrix, which you can adapt for use in your organization.

Examples of Progressive Discipline

A few familiar examples can illustrate the utility of progressive discipline for student behavior.

A student who is tardy to class once may get nothing more than an “Everything OK?” from the teacher. However, repeated tardies may result in a consequence such as detention or temporarily losing a privilege.

Similarly, a student who has a verbal altercation with another student may get little more than a warning and a chance to cool down the first time.

However, repeated aggression and physical fighting may lead to increasingly lengthy out-of-school suspensions and ultimately, expulsion.

Progressive discipline is not a new idea, but it has recently come under assault from well-intentioned but ill-informed reformers and vendors.

How Consequences Are Different from Punishment

Critics of consequences often attempt to conflate them with punishment.

There's some overlap, in that both punishment and consequences can dissuade students from taking actions that would violate school rules and disrupt the learning environment.

Both consequences and punishment work, in part, via operant conditioning, one of the best-known phenomena in psychology. B.F. Skinner, one of the founders of behaviorism, is perhaps the most widely known researcher associated with reinforcement and punishment.

But there are several key differences between consequences and punishment, and these differences make critiques of progressive discipline misguided.

First, punishment is intended to cause suffering—or at least a degree of unpleasantness—as a direct disincentive against repeating an unacceptable behavior.

Consequences, however, don't rely on unpleasantness for their effectiveness.

For example, a student who is suspended for fighting may actually enjoy staying home from school—especially if he has more free time to sleep and play video games.

Consequences instead derive their power from predictability:

If A, then B.

If I get in a fight at school, then I will get suspended.

This predictability creates a sense of procedural safety in organizations: while we can't prevent bad behavior from occurring, we can guarantee that we will always respond to it in a fair, measured way.

Predictable consequences also help students make good decisions about how they will behave, because they can do the math: if I don't want that consequence, I should avoid that behavior.

This brings us to the second difference: consequences are not tailored to the individual, while punishments typically are. We can treat all students fairly and consistently, without speculating about what will change their behavior.

A student who has never been in trouble before is likely to take detention very seriously. A student who has repeatedly gotten in trouble, in contrast, may be relatively unbothered by a detention.

Progressive discipline does not differentiate consequences based on the individual's projected reaction. The goal is not to cause suffering, but to reinforce a boundary.

Third, punishments may be ineffective for any given individual, and may have no positive impact on the learning environment, whereas consequences can uphold boundaries and protect the learning environment regardless of the individual's reaction.

Consequences Don't Always “Work”—And That's OK

Consequences may provide an incentive to modify one's behavior, but motivation is often not the issue for students who struggle the most.

Especially for students with chronic behavior issues, consequences may seem to make little difference.

So it's no wonder that educators often fret that consequences don't “work.”

In other words, consequences don't always prevent the behavior from occurring again.

Of course they don't.

Consequences obviously lack the power to overcome serious underlying issues that contribute to problematic behavior.

As compassionate educators who deeply care about our students, and want to help them succeed, we find this very distressing.

We want to do everything we can to help our struggling students, and consequences don't seem to help—they seem to make things worse.

But the purpose of progressive discipline is not to singlehandedly change the individual, which may not be a viable goal.

It would be naïve to expect a detention slip to overcome years of trauma.

The purpose of progressive discipline is to protect other people—and the organization's mission—from the consequences of individual misconduct, without being too harsh.

It may or may not help the individual student modify their behavior—and if it doesn't, the consequences will increase proportionally. These consequences can provide the leverage necessary for getting support for the student, such as mental health care.

How, then, do consequences ultimately work to protect the learning environment?

Consequences function to interrupt the individual's ability to have a negative impact on others.

Progressive discipline does not simply issue the same consequence over and over as the behavior recurs.

Instead, the consequence escalates as far as necessary—up to the point of expulsion—to protect the organization.

Why Escalating Consequences Are Necessary, And Why They Make Educators So Uncomfortable

It's important that organizations have policies in place to deal with repeated or escalating misconduct for a reason—because it has an escalating impact on the safe functioning of the organization.

When students experience more serious consequences as a result of their behavior, it's often distressing for educators—we tend to be quick to forgive and eager to move on.

We would often prefer to look the other way, or repeat a lower-level consequence, rather than see a student face greater repercussions for their actions.

However, this impulse to forgive and forget has consequences for everyone else—consequences that grow more dire as negative behavior escalates and spreads.

For example, students who are sent back to class after getting into a shouting match may soon be back in the office for getting into a fistfight that injured both themselves and others.

And if they aren't suspended, the violence may spiral out of control.

Failing to impose consequences may lead to real harm, but school consequences are not inherently harmful.

Critics of progressive discipline often make dramatic claims about the supposed negative impact of school consequences, but these claims do not withstand scrutiny.

No Need to Catastrophize: School Consequences Are Not Harmful

At the root of our discomfort with progressive discipline is the misconception that school-imposed consequences are actually injurious to students.

While this may have been true in the past—it's genuinely distressing to see corporal punishment in films like Little Women—we must not conflate removal from class and loss of privileges with physical beatings, humiliation, or other forms of harm.

To be clear, corporal punishment is still practiced in far too many places. It has no place in education, and should be eliminated immediately.

Similarly, humiliation and degradation have no place in school discipline. Progressive discipline must respect the dignity of the individual.

But requiring a student to sit calmly at a desk in a different room is not a form of cruel and unusual punishment.

Out-of-school suspension—sending a student home, where they already spend more than 80% of their time—is not abusive or harmful.

Letting a student know that what they've done is not acceptable—when the behavior occurred in full view of the class—is not a form of humiliation.

To be sure, anything can be done in a humiliating or degrading manner. Students always deserve their dignity and our respect, even when they've made a mistake.

But this does not mean removing consequences for behavior.

In life, behavior has consequences, and school is part of life.

If we shield students from the consequences of their actions at school—the setting where they interact with others the most—we inadvertently teach students a dangerous lesson about the consequences of violence and other harmful behaviors.

Consequences Do The Teaching

Approaches critical of progressive discipline, such as Dr. Becky Bailey's Conscious Discipline, often position “teaching” as an alternative to consequences.

The idea that we can “teach” good behavior is intuitively appealing to educators. It's certainly less unpleasant to teach a short lesson on pro-social behavior than to suspend a student.

But teaching is not merely presenting content or saying words. Students learn from our actions—what we do—more than what we say.

Consider a school that wants to stop students from hitting each other.

If we say “We don't hit” and teach lessons on getting along, we may think we're doing enough.

But if our actions demonstrate that students can, in fact, hit each other with impunity, students will learn a very different lesson than the one we intend.

We must actually follow through: we must make it impossible to hit—or engage in any other unacceptable behavior—with impunity.

How? By having predictable consequences.

Progressive Discipline Interrupts Impunity & Prevents Retaliation

In schools, we do everything possible to prevent violence from being met with violence.

We do not allow the victims of violence to reciprocate. Instead, we remove the perpetrator from the situation—both to protect the victim (and everyone else) from further harm, and to prevent retaliation.

Retaliation is far less likely when students can trust that school-imposed consequences will prevent students from hurting others with impunity.

Outside the school environment, there are no such protections. A student who is violent at home or in the community may face violent retaliation, with dire consequences.

Our ability to protect students outside of the school environment is limited to our influence on their choices. By teaching that actions have consequences—in school and out—we equip students to succeed in school and life.

But over the past few years, we seem to have lost sight of this important principle.

It's often pointed out that students who are repeatedly suspended from school get into trouble with the law or become victims of violence.

This is of course tragic, but attributing out-of-school tragedies to benign school discipline is to reverse cause and effect.

Bad Decisions Cause Suspension, Not Vice-Versa

Claims that progressive discipline is harmful to students make the error of confusing cause and effect.

For example, Boston NPR affiliate WBUR recently published a story in which an edtech researcher claims:

“[S]uspensions lead to lower academic performance for those students and an increased likelihood of them dropping out of school altogether.

When we look even at in-school suspensions or classrooms with high rates of exclusionary discipline, there's some interesting studies to show that not only is it worse for the student who is the recipient of that discipline, it's also worse for other students in the classroom.We see overall academic achievement go down in schools with high rates of punitive discipline.”

“How to fix the growing discipline problem in U.S. classrooms” On Point, WBUR

Researchers, too, have fallen into the trap of confusing correlation and causation.

Bad Data, Bad Conclusions

Researchers are often flummoxed by the limited availability of data on school discipline, and this leads to serious design flaws in many studies.

LiCalsi et al. (2021), for example, combined unusually detailed incident records from the NYC Department of Education with separate disciplinary consequence records in an attempt to isolate the effect of consequences.

However, the incident data set does not distinguish between perpetrators and victims, establishing a spurious relationship between consequences and other negative outcomes; obviously perpetrators of disciplinary incidents are likely to have worse outcomes than victims.

Other studies have found that school-issued consequences correlate with lower achievement. Why would we expect otherwise? It's no surprise that schools with high rates of disruptive behavior also have lower academic achievement.

Disruptive and violent behavior obviously has a negative impact on learning.

But which is more plausible:

- That consequences for bad behavior lead to lower academic performance, or

- That bad behavior itself leads to lower academic performance?

Obviously, schools that issue more consequences for bad behavior are likely to be schools that have more bad behavior.

But it's absurd to conclude that the consequence causes the behavior that prompted it.

How could policy experts, activists, and researchers make such a basic error in thinking about cause and effect?

It often comes down to one factor: US schools do not systematically collect or report any data on behavior. Instead, schools are required to report data on the consequences they issue—especially out-of-school suspensions and expulsions.

Lacking any data about behavior, researchers often use data on consequences as a proxy for data on behavior. But this makes it impossible to draw valid conclusions, or even conduct basic comparisons of schools and their approaches to discipline.

For example, consider two schools:

School A has excellent behavior, and only suspends a handful of students per year.

School B has awful behavior, and it is not dealt with effectively. As a result, the school suspends only a handful of students per year.

To researchers, these schools are indistinguishable in terms of their behavior data (which is really data on consequences).

To make matters worse, if School B starts addressing behavior and suspending students for the most egregious incidents, researchers may point out that its higher suspension rate is correlated with lower student achievement.

The “School-To-Prison Pipeline” Myth

Some have pointed to the correlation between school discipline and out-of-school trouble, such as arrest and incarceration, under the alarming moniker “school-to-prison pipeline.”

This, too, confuses correlation and causation.

Is it plausible that school-based consequences actually cause students to commit crimes outside of school?

Students are only in school for approximately 180 out of 365 days in the year—under 50%—and are in school for less than 1/3 of the 24-hour day.

Suspending a student for a few days makes no appreciable difference in the amount of time they have to get into trouble outside of school.

It's difficult to argue that, say, 21 additional hours of free time from a 3-day suspension, on top of the more than 7,000 hours students are already out of school in a year, causes them to get into trouble.

Suspension and other school-based consequences do not cause bad decisions.

Bad decisions cause the student to experience consequences, if effective progressive discipline policies are in place.

We must not confuse the direction of causality.

And yet, if we don't use progressive discipline, students will still face negative repercussions—the natural consequences of their poor choices.

We see this in school when students repay insult with insult, escalating a minor conflict into a major one.

As educators, we have a professional obligation to prevent conflict between students from escalating. Progressive discipline is our single most important tool for doing so.

If we find it too distasteful, and look the other way when we should intervene, disruption and violence are often the result.

Our discomfort with harmless school consequences can result in actual harm—but this harm is easy to overlook.

Failing to use progressive discipline often has no obvious short-term effects.

Simply sending a student back to class after they've had a chance to “cool down” may seem like the path of least resistance.

But as we're seeing in a growing number of schools, the collective impact of failing to impose progressive discipline is catastrophic—students disrupt the learning of others, get into further conflicts, and create an environment in which teaching and learning are impossible.

Your School Already Has A Progressive Discipline Policy

Nearly all schools and districts currently have progressive discipline policies on the books.

While a few organizations may have recently revised their policies to eliminate escalating consequences for repeated or more severe misbehavior, most have not.

Progressive discipline is not a new or radical idea; it's how school discipline has always worked.

What is new is the wide range of proactive supports and interventions schools are putting in place to address harmful behaviors.

While many of these practices are promising, they must supplement rather than replace progressive discipline.

What About Equity?

Opposition to progressive discipline is often rooted in well-intentioned efforts to create equitable outcomes and address disproportionality in discipline statistics.

This is an important priority, but there are no shortcuts. Trying to address disproportionality by tinkering with progressive discipline can only make matters worse.

Disproportionality can have two distinct causes:

- Unfair treatment, in the form of inconsistent application of discipline policy to different groups of students. This is historically well-documented, and absolutely needs to be addressed if it's occurring.

- Different rates of incidence—for example, it's widely acknowledged that boys are involved in violent altercations at far higher rates than girls. Boys may need more deliberate preventative measures, such as social skills instruction, to reduce violent altercations.

It's important to understand that equity cannot be achieved at the stroke of a pen.

We cannot solve a problem with fistfights between boys by downgrading them to “disagreements.”

If we're being too harsh with one group of students, that's something we can fix.

But if the problem is different rates of incidence, we must invest in prevention, not overlook the behavior.

Combining Support and Consequences

Discipline and intervention are not mutually exclusive.

New York superintendents recently defended the need for suspension in some cases, but noted that there are alternatives, like in-school suspension, that can provide support as well:

Superintendents described changing their in-school suspension rooms to voluntary spaces where students could receive counseling and help from trained professionals. They outlined efforts to teach social-emotional skills — everything from managing difficult emotions to getting along with others — as a way of reducing the unsafe behaviors that can lead to suspensions.

Times-Union: “School superintendents: Don't ban all long-term suspensions”

Progressive discipline is not at odds with efforts at prevention and support.

It's terrific that an enormous amount of effort is being poured into efforts like:

- Trauma-informed practice

- Restorative circles

- Social-emotional learning

- Culturally responsive practice

- Peer mediation

- Counseling and mental health services

As evidence emerges about the effectiveness of these programs, it's important for schools to invest appropriately in the supports their students need.

But nothing can replace the need for progressive discipline. It will always be necessary to have consequences for harmful and disruptive behavior.

As one superintendent explained:

“I had to suspend a student a week and a half ago for selling drugs out of my bathroom. There was no (trauma or mental illness) there.”

It's also important for researchers to study school discipline using more robust methods—not just looking at consequence and academic achievement data, which are easy to obtain, but don't tell the whole story.

Getting Parents To Take Action

School discipline can also serve as a much-needed wake-up call for parents, forcing them to get their children the help they need.

For example, long-term suspensions can be reduced in length if parents agree to seek services for their children as part of a behavior contract:

The contracts sometimes require families to get their children mental health care.

“We can’t mandate that,” Superintendent Daryl McLaughin said, explaining that it’s allowed if the family agrees to it voluntarily in a contract.

McLaughlin leads the Perry Central School District in western New York. He said there’s a lack of mental health resources in his rural area, but that the contracts are working.

“Our recidivism rates have dropped,” he said, adding that districts can use long-term suspensions as a “re-engagement measure” by requiring certain actions in the contracts.

Times-Union: “School superintendents: Don't ban all long-term suspensions”

Progressive Discipline For Adults

Many of the concepts above apply to adult behavior as well, though the applicable policies are different.

A teacher who snaps at a colleague once may be asked to take a breather, with no formal HR action, but a teacher who's chronically abusive to teammates needs to be guided through an improvement process, and if that doesn't lead to change, may need to find other employment.

A parent who's rude on the phone may be tolerated to an extent, but a parent who comes into the office screaming curses and threats of violence may need to be escorted from the premises and served with a no-trespass order.

Other people tell us how they need to be treated based on their behavior.

As leaders, we must have the courage to protect the people and the work we're responsible for.

Fixing A Broken Progressive Discipline System

What if progressive discipline has already broken down, and people are acting with impunity?

In most cases, it's only practice that has changed—not policy.

If it has become unfashionable to, say, suspend students for fighting, and instead send them back to class after they've had a chance to “cool down,” the first step is to simply start following existing policies.

If you haven't been suspending students for serious misbehavior, you can start immediately.

As leaders, we must be willing to make our statistics worse on paper in order to make reality better for the people who must live in the environments we're responsible for.

We must also be willing to take unpleasant action to deal with unacceptable adult behavior.

Formal warnings and reprimands are among the most unpleasant tasks that fall to school administrators, but they may be necessary for addressing toxic, harmful behaviors.

What if the policies have already been changed, and progressive discipline is no longer possible?

Banning out-of-school suspension is a hot topic, with many states considering partial or total bans.

Bo Wright, a superintendent in update New York, says that such policies make things worse, not better:

Wright has worked at several districts that tried capping or banning suspensions.

“In terms of actually addressed behavior and building school culture and making school safer, in my experience, it had the opposite effect,” he said.

Times-Union: “School superintendents: Don't ban all long-term suspensions”

Districts often strive to be the first to experiment with new policies, such as banning out-of-school suspension, out of a belief that they're taking the best possible course of action for students.

These experiments will play out over time, and in the meantime, this may leave educators in an untenable situation.

If your organization is unwilling to support you in addressing misconduct with progressive discipline, it's worth raising the issue and, as the principle itself suggests, being willing to take stronger action if necessary—even if it means finding a more supportive employer.

This information is provided for general information only, and does not constitute legal advice.

About the Author

Justin Baeder, PhD is Director of The Principal Center, where he helps senior leaders in K-12 organizations build capacity for instructional leadership by helping school leaders:

- Confidently get into classrooms every day

- Have feedback conversations that change teacher practice

- Discover their best opportunities for student learning

He holds a PhD in Educational Leadership & Policy from the University of Washington, and is the host of Principal Center Radio, where he interviews education thought leaders.

His book Now We're Talking! 21 Days to High-Performance Instructional Leadership (Solution Tree) is the definitive guide to classroom walkthroughs, and his book Mapping Professional Practice (with Heather Bell-Williams) helps instructional leaders create instructional frameworks to establish shared expectations for practice.

Progressive is a term that can have various meanings depending on the context in which it is used.