K-12 leaders must abandon the delusion of “data-driven” decision-making, and instead embark on a serious evidence-driven overhaul of learning, teaching, and leadership.

With learning in particular, we don’t have much evidence of learning because we are have replaced too much content with skills that aren’t really skills. We’ve tried to get students working on higher-order cognitive tasks, without giving them the knowledge they need to do those tasks.

As a result, we don’t really have much evidence of learning. And without evidence of learning, we have a limited ability to connect teacher practice to its impact on student learning. When we don’t know how we’re impacting teacher practice, we don’t have evidence of improvement. We have only data—and data can’t tell us very much.

The Data Delusion

Beginning in earnest with the passage of No Child Left Behind, our profession embarked on a decades-long crusade to make K-12 education “data-driven,” a shift that had already been underway in other fields such as business and public health.

To be sure, bringing in data—especially disaggregated data that helps us see beyond averages that mask inequities—was an overdue and helpful step. But we went too far in suggesting that data should actually drive decisions about policy and practice. Should data inform our decisions? Absolutely. But the idea that data should drive them is absurd.

Imagine making family decisions “driven” by data. Telling your spouse “We need to make a data-driven decision about which grandparents to visit for the holidays” is both unworkable on its face, and an approach that misses the point of the decision. Data might play a role—how much will plane tickets cost? How long of a drive is it? How many days do we have off from school?—but letting data drive the decision would be wrong.

And we’d never advise our own teen, “Honey, just make a spreadsheet to decide who to take to prom.” I’m sure we all know someone who did that, but it’s not a great way to capture what really matters.

We know intuitively that we make informed judgments holistically, based on far more than mere data. Yet it’s a truth we seem to forget every time we advocate for data-driven decision-making in K-12 education.

Knowing Where We’re Going: The Curriculum Gap

The idea of collecting data becomes even more ridiculous when we consider the yawning gap in many schools: a lack of a guaranteed and viable curriculum. When we aren’t clear on what teachers are supposed to be teaching—and what students are supposed to be learning—teaching is reduced to abstract skills that can supposedly be assessed by anyone with a clipboard.

No less a figure than Robert Marzano has stated unequivocally “The number one factor affecting student achievement is a guaranteed and viable curriculum” (What Works In Schools, 2003). Historically, having a guaranteed and viable curriculum has meant that educators within a school would generally have a shared understanding of what content students would be taught and expected to learn.

For some reason, though, the idea of content has fallen out of fashion. We’ve started to view teaching as a skill that involves teaching skills to students, rather than a body of professional knowledge that involves teaching students a body of knowledge, and layering higher-order intellectual work on top of that foundation of knowledge.

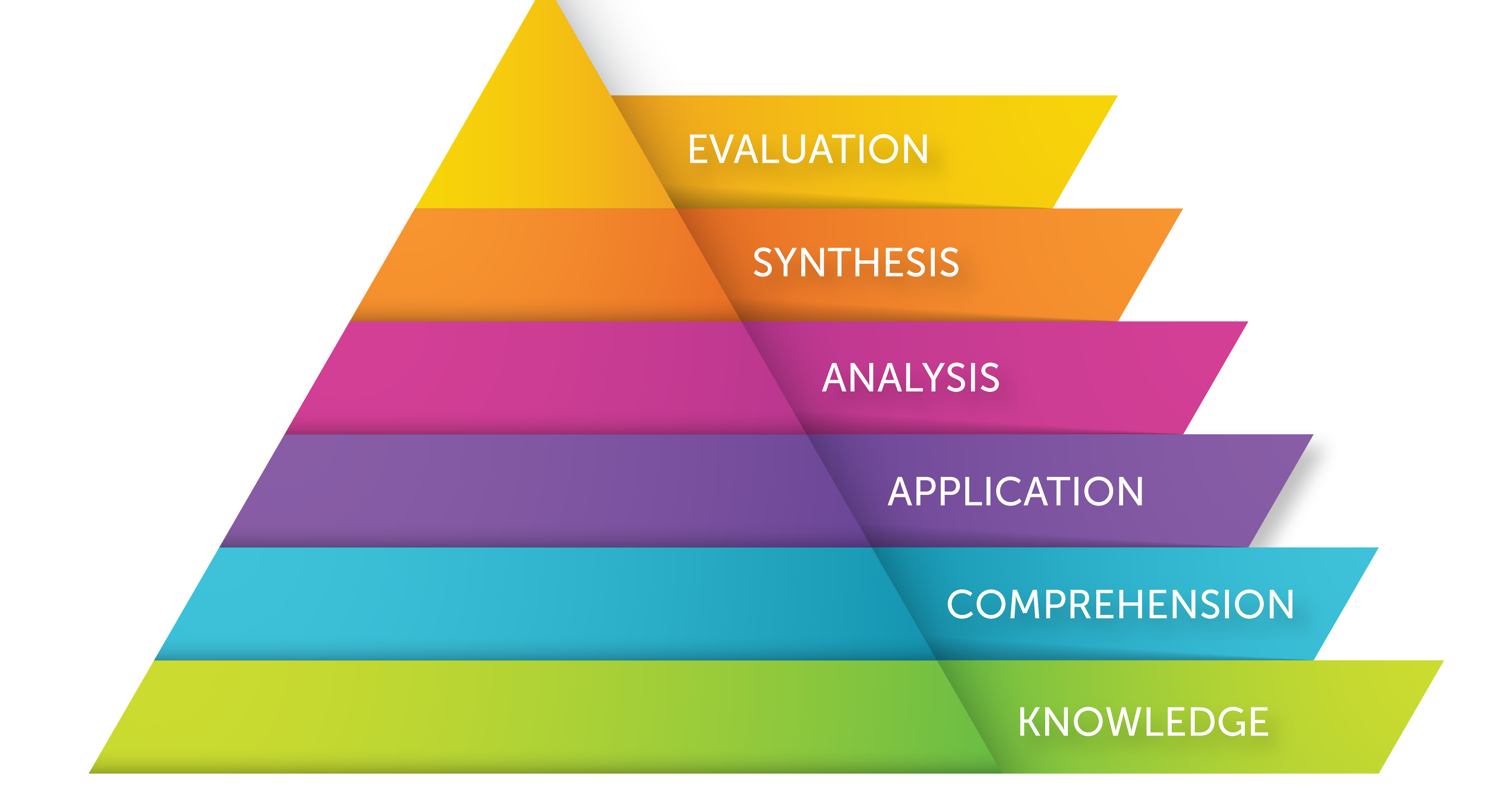

I attribute this fad to a popular misconception about Bloom’s Taxonomy (or if you prefer, Webb’s Depth of Knowledge): the idea that higher-order cognitive tasks are actually better, and shouldn’t be just the logical extension of more foundational tasks like knowing and comprehending, but should actually replace them.

This misconception has spread like wildfire through the education profession because next-generation assessments—like those developed by the PARCC and SBAC consortia to help states assess learning according to the Common Core State Standards—require students to do precisely this type of higher-order intellectual work.

There’s nothing wrong with requiring students to do higher-order thinking—after all, if high-stakes tests don’t require it, it’s likely to get swept aside in favor of whatever the tests do require (as we’ve seen with science and social studies, which have been de-emphasized in favor of math and reading).

The problem is that we’re no longer clear about what knowledge we want students to do their higher-order thinking on—largely because the tests themselves aim to be content-neutral when assessing these higher-order skills.

Starting in the 1950s, Benjamin Bloom convened several panels of experts to develop the first version of his eponymous taxonomy:

It’s no accident that Bloom’s model is often depicted as a pyramid, with the higher levels resting on the foundation provided by the lower levels. Each layer of the taxonomy provides the raw material for the cognitive operation performed at the next level.

“Reading comprehension” is not a skill that can be exercised in the abstract, because one must have knowledge to comprehend; you can’t comprehend nothing. That’s why, as Daniel Willingham notes, reading tests are really “knowledge tests in disguise” (Wexler, 2019, The Knowledge Gap, p. 55).

The preference for “skills” over knowledge is explored in depth in one of the best books I’ve read this year, Natalie Wexler’s The Knowledge Gap: The Hidden Cause of America's Broken Education System—and How to Fix It. She explains:

[S]kipping the step of building knowledge doesn’t work. The ability to think critically—like the ability to understand what you read—can’t be taught directly and in the abstract. It’s inextricably linked to how much knowledge you have about the situation at hand.

p. 39

Wexler argues that we’ve started to treat as “skills” things that are actually knowledge, and as a result, we’re teaching unproven “strategies”—in the name of building students’ skills—rather than actually teaching the content we want students to master. Wexler isn’t arguing for direct instruction, but rather the intentional teaching of specific content—using a variety of effective methods—rather than attempting to teach “skills” that aren’t really skills.

For example, most educators over the age of 30 mastered the “skill” of reading comprehension by learning vocabulary and, well, reading increasingly sophisticated texts—with virtually no “skill-and-strategy” instruction like we see in today’s classrooms. Somehow, the idea that we should explicitly teach students words they’ll need to know has become unpalatable, even regressive in some circles.

In a recent Facebook discussion, one administrator wondered in a principals’ group “Why are students still asked to write their spelling words 5 times each during seat work??” Dozens of replies poured in, criticizing this practice as archaic at best—if not outright malpractice. Clearly, learning the correct spelling of common words is a lower-level cognitive task, but it’s one that is absolutely foundational to literacy and success with higher-order tasks, like constructing a persuasive argument.

This aversion to purposefully teaching students what we want them to know is driven by fads among educators, not actual research. Wexler writes:

[T]here’s no evidence at all behind most of the “skills” teachers spend time on. While teachers generally use the terms skills and strategies interchangeably, reading researchers define skills as the kinds of things that students practice in an effort to render them automatic: find the main idea of this passage, identify the supporting details, etc. But strategies are techniques that students will always use consciously, to make themselves aware of their own thinking and therefore better able to control it: asking questions about a text, pausing periodically to summarize what they’ve read, generally monitoring their comprehension.

Instruction in reading skills has been around since the 1950s, but—according to one reading expert—it’s useless, “like pushing the elevator button twice. It makes you feel better, perhaps, but the elevator doesn’t come any more quickly.” And even researchers who endorse strategy instruction don’t advocate putting it in the foreground, as most teachers and textbook publishers do. The focus should be on the content of the text.

p. 56-57

Part of the problem may be that the Common Core State Standards in English Language Arts mainly emphasize skills, while remaining agnostic about the specific content used to teach those skills. This gives teachers flexibility in, say, which specific novels they use in 10th grade English, so it isn’t necessarily a flaw—unless we make the mistake of omitting content entirely, in favor of teaching content-free skills.

(The Common Core Math Standards, in contrast, make no attempt to separate content from skills, and it’s obvious from reading the Standards that the vocabulary and concepts are inseparable from the skills.)

Yet separating content and skills is precisely what we’ve done in far too many schools—and not just in language arts. Seeking to mirror the standardized test items students will face at the end of the year, we’ve replaced a substantive, content-rich curriculum with out-of-context, skill-and-strategy exercises that contain virtually no content. We once derided these exercises as drill-and-kill test prep, yet somehow they’ve replaced actual content.

Even more perversely, teaching actual content has become unfashionable to the point that content itself has become the target of the “drill-and-kill” epithet.

As a result of these fads, many schools today simply lack a guaranteed and viable curriculum in most subjects, with the notable exception of math.

Is Teaching A Skill?

For administrators, the view that students should be taught skills rather than content is paralleled by a growing belief that teaching is a set of “skills” that can be assessed through brief observations.

This hypothesis was put to the test by the Gates-funded Measures of Effective Teaching project, which spent $45 million over a period of three years recording some 20,000 lessons in approximately 3,000 classrooms. Nice-looking reports and upbeat press releases have been written to mask the glaring fact that the project was an abject failure—we are no closer to being able to conduct valid, stable assessments of teacher skill than before.

Why did MET fail to yield great insights about teaching? Because it misconstrued teaching as a set of abstract skills rather than a body of professional practice that produces context-specific accomplishments. Every principal knows that there’s an integral relationship between the teacher, the students, and the content that “data” (such as state test scores) fail to capture.

We cannot “measure” teaching as an abstract skill, because it’s not an abstract skill. Teachers always teach specific content to specific students—and the specifics are everything. Yes, there are “best practices,” but best practices must be used on specific content, with specific students—just as reading comprehension strategies must be used on a specific text, using one’s knowledge of vocabulary, along with other background knowledge about the subject matter.

Teaching is not an abstract skill in the sense that, say, the high dive is a skill. It can’t be rated with a single score the way a high dive can. Involving more “judges” doesn’t improve the quality of any such ratings we might want to create.

A given teacher’s teaching doesn’t always look the same from one day to the next, or from one class to the next, and it can’t be assessed as if there existed a “platonic ideal” of a lesson.

To understand the root of the “guaranteed and viable curriculum” problem as well as the teacher appraisal problem, we don’t have to dig very far—Bloom’s Taxonomy provides a robust explanation.

Bloom’s Taxonomy and the “Data-Driven Decision-Making” Problem

Neither Bloom’s Taxonomy or Wexler’s Knowledge Gap focuses specifically on teacher evaluation, but the parallels are clear. Principals who regularly spend time in classrooms, building rich, firsthand knowledge of teacher practice are in a far better position to do the higher-order instructional leadership work that follows. Knowledge—the foundation of the pyramid—that has been comprehended can then be applied to different situations, and principals who repeatedly discuss and analyze instruction in post-conferences with teachers will be far more prepared to make sound evaluation decisions at the end of the year.

On the other hand, it’s impossible to fairly analyze and evaluate a teacher’s practice based on just one or two observations or video clips, because such a limited foundation of knowledge affords observers very little opportunity to truly comprehend a teacher’s practice.

Using Bloom’s Taxonomy to understand the failure of the MET project is straightforward, because the resulting diagram is decidedly non-pyramidal: an enormous amount of effort went in to the analysis, synthesis, and evaluation of a very small amount of knowledge of teacher practice, with very few efforts to comprehend or apply insights about the specific instructional situation of each filmed lesson. It’s more of a mushroom than a pyramid.

By treating teaching as an abstract skill that can be filmed and evaluated—apart from even the most basic awareness of the purpose of the lesson, its place within the broader curriculum, students’ prior knowledge and formative assessment results, and their unique learning needs—the MET project perpetuated the myth that education can be “data-driven.”

It’s time to call an end to the “data-driven” delusion. It’s time to take seriously our duty to ground professional practice in evidence, not just data. It’s time to ensure that all students have equitable access to a guaranteed and viable curriculum. It’s time to treat student learning and teacher practice as the primary forms of evidence about whether a school is improving—and reduce standardized tests to their proper role as merely a data-provider, and not a “driver” of education.

As leaders, we need clear, shared expectations for student learning and teacher practice. We need direct, firsthand evidence. Only then can we make the right decisions on behalf of students.