At the Principal Center, we frequently get questions about the best way to approach classroom walkthroughs and informal observations.

In this article, Dr. Justin Baeder, author of Now We're Talking! 21 Days to High-Performance Instructional Leadership, summarizes his advice in response to reader questions.

Learn more about Now We're Talking! »

What kind of walkthroughs should I do?

There are many approaches to walkthroughs, from casual “smile and wave” visits aimed at visibility, to more in-depth mini-observations.

In Now We're Talking! 21 Days to High-Performance Instructional Leadership, I recommend making visits that are in the sweet spot:

- Frequent—18 biweekly visits per teacher per year

- Brief—around five to fifteen minutes

- Substantive—more than just making an appearance

- Open-ended—focused on the teacher’s instructional decision-making, not just narrow data collection

- Evidence-based—centered on what actually happens in the classroom

- Criterion-referenced—linked to a shared set of expectations

- Conversation-oriented—designed to lead to rich conversations between teachers and instructional leaders

These characteristics are described in Chapter 2 of Now We're Talking, and contrasted with other models for classroom walkthroughs in Chapter 3.

Get the book + instant access to the audiobook with the Instructional Leadership Challenge »

What should my purpose be when visiting classrooms?

Visiting classrooms has two primary benefits:

- Building strong professional relationships with teachers

- Providing decisional information you can use as an instructional leader

While you may sometimes have the chance to provide useful feedback, it's best to have modest expectations for yourself—especially for very brief visits.

When considering your feedback, keep in mind the “Hippocratic Oath” for instructional leaders: Seek first to understand, then to be understood. (Covey's 5th Habit)

How often should I get into classrooms?

If you're a school-based administrator, I recommend visiting 3 classrooms a day. This will get you into 15 classrooms a week, which for most administrators means seeing every teacher every two weeks or so.

Over the course of a year, that adds up quickly—to 500 or so visits in all.

If you'd like, we can send you a free #500Classrooms sticker to help you stay on track—request one here.

Should I leave a note?

Teachers often appreciate short, positive notes from their administrators, so it certainly doesn't hurt.

Here's a simple template you can use to make blank notecards with your school mascot or logo on the front.

Swap in your mascot or logo, print on card stock, cut, and fold.

However, keep any notes you leave simple and positive—don't ask detailed questions or give critical feedback.

The harder you make it for yourself, the less frequently you'll get into classrooms, so don't hold yourself to leaving a note—and if you do, keep it very simple.

Read on for more about how to conduct high-impact walkthroughs.

How long should my visits be?

5-15 minutes is usually an ideal range—long enough to fuel a substantive conversation, but short enough to be doable. 10 minutes is a good target.

A law of diminishing returns applies—the longer you stay, the less new information you'll learn with each passing minute.

The shorter you keep your visits, the easier it'll be to stay on track while dealing with interruptions in a timely manner.

What should I look for in my walkthroughs?

While walkthroughs can give you a general sense of the classroom environment, the most important thing to focus on is the teacher's instructional purpose.

As you observe, ask yourself:

- What's this lesson about? What is the teacher trying to accomplish?

- What is the teacher doing, what are the students doing, and how does that fit with the teacher's purpose?

These aren't questions to ask the teacher, but rather to focus your own attention on noticing the right things.

Should I give positive & negative feedback?

There's a widespread myth that instructional leaders should leave a “feedback sandwich” consisting of:

- A compliment—something the teacher did well

- A suggestion for improvement, and

- Another compliment

This artificial has several drawbacks.

First, it's actually quite hard to think of compliments and suggestions that will be helpful rather than insulting or patronizing. Forcing yourself to use the feedback sandwich tends to lead to avoiding classroom walkthroughs altogether.

Additionally, teachers are likely to be unclear whether your compliments and suggestions are to be taken seriously, or just a formality you feel obligated to deliver.

Instead, have an authentic conversation by asking good evidence-driven questions.

In your feedback conversations, you can move flexibly between three roles:

- The boss role, in which you tell—giving directive feedback to change teacher behavior

- The coach role, in which you ask—using reflective questions to change teacher thinking

- The leader role, in which you listen and change the circumstances teachers are working under.

Learn more about these three roles in this ASCD Express article: Go and See—The Key To Improving Teaching & Learning »

Should I use an observation checklist?

While observation checklists are common, I am not aware of any research supporting their use, and I don't recommend them.

Whatever is on a given checklist is unlikely to be visible in any given 10-minute observation—even the best teachers don't do everything all the time.

Evaluation criteria, like Charlotte Danielson's Framework for Teaching, are designed to describe teachers' overall practice, not single lessons or parts of lessons.

Checklists are best used for simple compliance purposes—for example, a checklist is the ideal tool for your custodian to make sure each classroom has a working fire extinguisher— but they're not very helpful for professional growth.

Instead, I recommend using an evidence-driven approach, and focusing on what actually happens while you're in the room, rather than noting all the things that aren't happening.

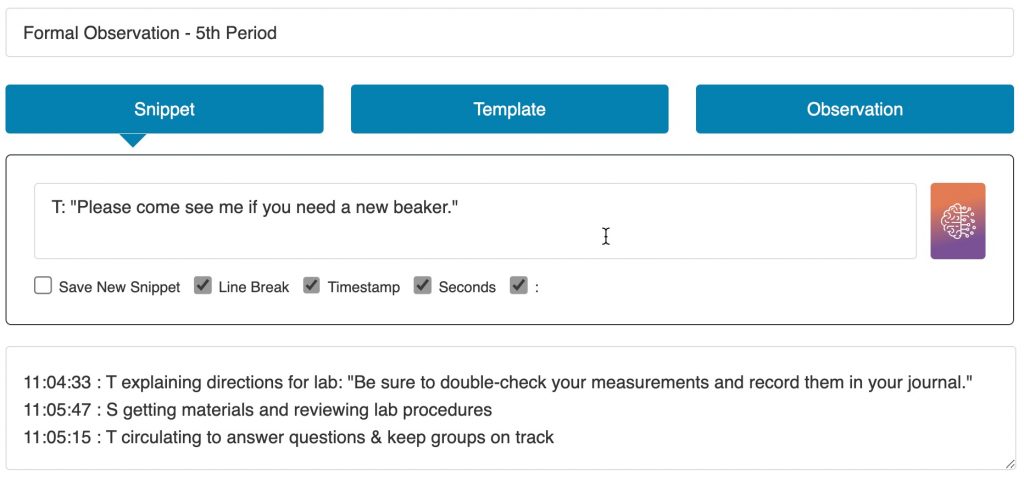

For documenting what is happening, it's best to take detailed notes; a checklist would only give a yes/no binary, which wouldn't be very useful in your conversation with the teacher afterward.

What if I can't come up with very good feedback, especially in subjects I haven't taught?

As instructional leaders, we often have unrealistic expectations that we'll be able to give life-changing, earth-shattering feedback every time—an illusion we can only sustain by failing to get into classrooms.

When you get into classrooms every day, you'll realize that you often don't have the perfect feedback for every teacher. That's OK—don't let the perfect be the enemy of the good.

I believe it's a mistake to use the term feedback to mean “critique.” Giving teachers feedback does not necessarily mean telling them what they're doing well and what they should do differently.

Feedback is really an audio term—it's the process of amplifying and returning information to its source for the purpose of monitoring and making adjustments.

So you don't need to have any specific suggestions for a teacher when you give feedback—simply share what you noticed, and ask good questions (see below) to get the teacher talking and thinking.

You don't have to take notes, but if you are taking notes, giving them to the teacher is an important step to build trust and minimize fear.

Which teachers should I visit?

If you're a school-based administrator, I recommend rotating your visits among each teacher you supervise.

While the span of supervision (number of direct reports) varies widely across the profession, most administrators are responsible for evaluating 20 to 40 teachers.

Taking 30 as an average number of teachers, visiting 3 classrooms a day will get you around to each teacher you supervise once every 10 days, or two school weeks—an ideal frequency.

Should I visit the teachers I don't evaluate?

No. If you share supervision and evaluation duties with other administrators on your team, visit only the teachers you supervise.

While it may be appealing—especially for principals who don't want to be completely unfamiliar with the teachers evaluated by assistant principals—to include all teachers in your rotation, the numbers are simply too great, which drops the frequency of visits below a critical threshold.

While it's helpful to know what's going on in every classroom, there are other, more manageable strategies that can provide this insight.

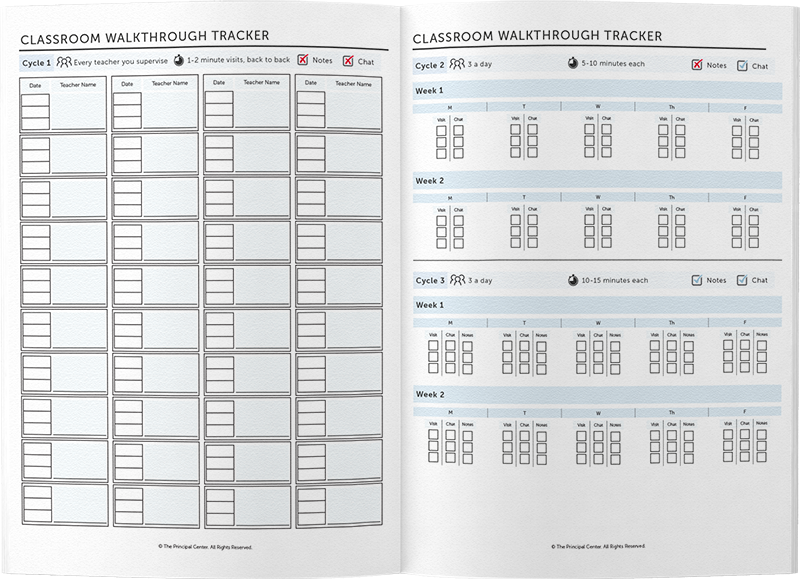

How can I keep track of my visits?

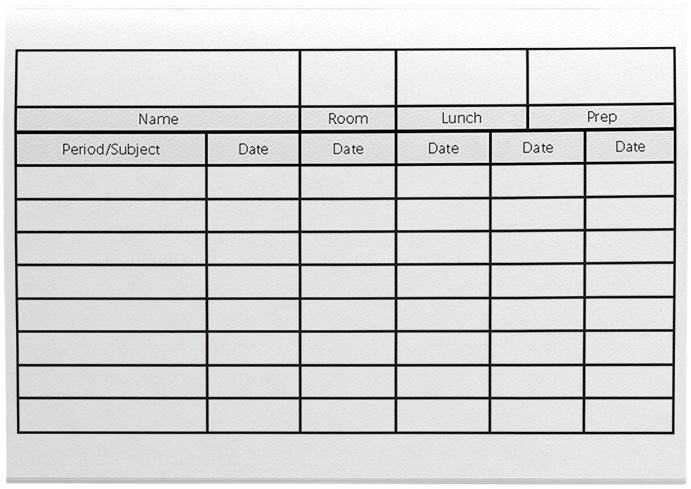

Print our Classroom Walkthrough Tracker to start getting into classrooms immediately.

Use the first page to record each teacher's name and the date of your visits.

Important: visit teachers in the same order each cycle, so they don't feel that you're targeting them.

What kind of documentation should I provide?

Don't worry about providing written feedback at all. Simply document the date and time of your visit, so you know which teachers you've visited and which you haven't.

A simple way to keep track of your visits is with our Classroom Visit Index Cards template.

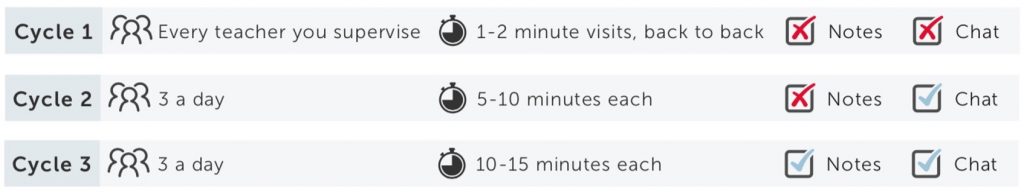

After you've visited each teacher once, you can start to engage in more substantive conversations and take notes, but in your first two cycles of visits, don't take notes provide any written feedback at all.

What form should I use?

While walkthrough forms are popular, no research has ever indicated that walkthrough forms are an effective practice for instructional leaders.

Forms are impersonal and tend to be poorly received by teachers. Instead, simply have a face-to-face conversation.

Sharing your verbatim notes via email can also be helpful, starting in your 3rd cycle of visits, as described in the 3-Cycle Startup Plan.

You can use the simple notecard system above to track your visits, or if you prefer to use Google Forms to record your visits, here's a step-by-step article on how to do so.

How can I get teachers to be more receptive to my visits?

At first, teachers may be unclear about the purpose of your visits, or even fearful of “gotcha” observations.

Even with the best of intentions, too many leaders come on too strong and face pushback from teachers, causing them to abandon their efforts.

To minimize teacher fear and resistance, I recommend ramping up your visits across three cycles.

Get the Classroom Walkthrough Tracker by taking the Instructional Leadership Challenge »

In your first round of visits, don't take any notes or give any feedback. Just show up with a smile on your face and stay for a few minutes, with the goal of being present and pleasant.

If nothing bad happens when you visit, teachers' fears will start to subside. But it's crucial not to trigger their fear of being singled out by visiting every teacher once before visiting any teacher a second time. When teachers check with each other, and realize they're not the only one you're visiting, they'll be far less worried.

In your second cycle, visit teachers in the same order. Pay closer attention, and chat briefly afterward, to show that you're interested in what teachers are doing, but don't give any critical feedback or take notes.

After your second cycle, you can make an announcement in your staff newsletter, an email, or a faculty meeting. You might say something like:

I've really enjoyed getting into classrooms over the past few weeks to see all the great learning that's taking place. I'm learning so much about where we are as a school, and what we're already doing that's working. To continue my learning, and to give me more context for understanding your practice as a professional, I'm planning to continue my classroom visits, and if you see me taking notes, you can expect me to give you a copy. I hope we can have a chance to talk each time I visit, but if that's not always possible, feel free to set up a time with me or chat via email.

Important: do NOT say your visits are “non-evaluative” even if they're not formally part of the evaluation process. You want to set a low-key expectation, but it's usually not true that your informal walkthroughs won't shape your final evaluations in any way.

In your third cycle, you can start taking notes, and as long as you're sharing them with the teacher immediately, this shouldn't cause undue stress, because you've worked up to it.

Should I differentiate my walkthroughs, and make more frequent visits to teachers I'm concerned about?

No—at least, not as part of your practice of classroom walkthroughs.

If you have teachers on a formal plan of improvement, you may need to observe them more often, but for routine walkthroughs, it's best to visit everyone equally and in the same order in each cycle.

Visiting some teachers more than others can trigger fears of targeting or harassment. That's why I recommend visiting teachers in a specific order, so you don't over- or under-visit anyone.

How can I give good feedback to teachers who teach grades or subjects I've never taught?

This was my situation as a principal—I was an elementary principal who had been a middle school science teacher, but never an elementary teacher. This forced me to be humble and curious—habits that served me well even as my knowledge of best practice in the elementary grades grew.

Getting into classrooms—simply paying attention and asking good questions—is one of the best forms of professional development for instructional leaders. If you use the evidence-based feedback questions below, you'll learn a great deal from each conversation.

You can also attend the same trainings teachers are attending to build your content knowledge—especially initial-use trainings for new curriculum your school is adopting.

And of course, there's no substitute for staying current on the latest books and research. I recommend listening to any of the more than 300 authors we've featured on Principal Center Radio.

What kinds of questions should I ask in feedback conversations?

There are two important priorities for the questions you ask in feedback conversations:

- Focus on specific evidence

- Get the teacher talking

Rather than ask leading questions like “Have you thought about…?” it works best to ask open-ended questions that get the teacher talking, but that start with specific evidence from your visit.

Here are 10 questions you can use—simply share [something you noticed] when you see [ ]:

- Context: I noticed that you [ ]…could you talk to me about how that fits within this lesson or unit?

- Perception: Here’s what I saw students [ ]…what were you thinking was happening at that time?

- Interpretation: At one point in the lesson, it seemed like [ ]… What was your take?

- Decision: Tell me about when you [ ]… What went into that choice?

- Comparison: I noticed that students [ ]… How did that compare with what you had expected to happen when you planned the lesson?

- Antecedent: I noticed that [ ]… Could you tell me about what led up to that, perhaps in an earlier lesson?

- Adjustment: I saw that [ ]… What did you think of that, and what do you plan to do tomorrow?

- Intuition: I noticed that [ ]… How did you feel about how that went?

- Alignment: I noticed that [ ]… What links do you see to our instructional framework?

- Impact: What effect did you think it had when you [ ]?

Download as a PDF: 10 Questions for Better Feedback on Teaching »

How should I rate teachers?

Having clear teacher evaluation criteria, like the Danielson Framework, is essential.

However, it's crucial to remember what we're evaluating: the teacher's overall practice.

They're teacher evaluation criteria, not lesson evaluation criteria. This means we shouldn't attempt to rate or score individual lessons.

Instead, base your year-end evaluations on the overall picture you have of each teacher's performance.

Leaders who visit classrooms every day will have far more evidence to work with, and a far more accurate picture of each teacher's strengths and weaknesses.

Visiting just 3 classrooms a day, for an average of 10 minutes each, will get you into each teacher's classroom about 18 times per year (if you have 30 teachers and a 180-day school year).

That's 180 minutes from walkthroughs, plus whatever formal observations you do—giving you at least 4x the total time you'd spend in each teacher's classroom for formal observations alone.

Plus, there's a huge difference in sampling—when you make frequent, unannounced visits, you'll get a much truer picture of each teacher's typical practice, since there's no pressure or opportunity to put on a show like there is for a formal observation.

To keep track of your progress toward completing teacher evaluations, download our free Teacher Evaluation Organizer spreadsheet.

How can I make time to get into classrooms?

The conventional wisdom is to “block off time” on your calendar.

If this approach is already working for you—meaning you're able to get into classrooms every day—that's great.

For most people, though, interruptions make it impossible to consistently visit classrooms at a specific time.

So instead, identify 4 to 6 times on your calendar for getting into classrooms daily, e.g. before lunch, after recess, in the middle of 5th period—whatever works based on your existing schedule.

The more you can add visits right before or right after existing commitments, such as meetings and duties, the less you'll get interrupted.

How can I spread effective practices from one classroom to another?

Even with no outside professional development, most schools could improve dramatically by simply sharing more effective practices within the building.

If you see an effective strategy, you can recommend it to another teacher—with or without giving the first teacher credit. Sometimes it's awkward to be held up as an example before your peers, so it's better not to say where you learned about an approach.

You can also share best practices in your staff newsletter, faculty meetings, and other settings for professional learning.

What should district leaders hold principals accountable for?

The most important measure of success is frequency of classroom visits. While the content and quality of feedback can vary greatly, it doesn't matter if it's not happening at all, so the first priority is actually getting into classrooms.

The best way to ensure that principals are getting into classrooms is to look at their records, e.g. notecards showing the dates of visits to teach teacher.

Have other questions? Leave a comment.

Leave a comment below if you have other questions about classroom walkthroughs.

About the Author

Justin Baeder, PhD is Director of The Principal Center, where he helps senior leaders in K-12 organizations build capacity for instructional leadership.

A former principal in Seattle Public Schools, he is creator of the Instructional Leadership Challenge, which has helped more than 10,000 school leaders in 50 countries around the world:

- Confidently get into classrooms every day

- Have feedback conversations that change teacher practice

- Discover their best opportunities for school improvement

Dr. Baeder is the author of Now We're Talking! 21 Days to High-Performance Instructional Leadership, and the co-author, with Heather Bell-Williams, of Mapping Professional Practice: How to Develop Instructional Frameworks to Support Teacher Growth (Solution Tree).

He is the host of Principal Center Radio, a podcast featuring education thought leaders, and the founder of Repertoire, the professional writing app for instructional leaders.

He holds a PhD in Educational Leadership & Policy Studies from the University of Washington and an MEd in Curriculum & Instruction from Seattle University, and is a graduate of the Danforth Program for Educational Leadership at UW.

Thank you so much for this article. I am a new AP and this has been such a help to me as I begin the school year.