Suspension has been misapplied so often that it's wrongly gotten a bad rap. It's time to rethink its proper role in K-12 schools.

In the small number of cases where it's the right response to severe misbehavior, it's an essential tool for protecting the learning environment.

At the same time, many schools have a long history of using suspension inappropriately and applying consequences unfairly based on race.

Here's how school administrators can use suspension effectively to protect the learning environment, while addressing bias and other problems.

By Justin Baeder, PhD

Suspension Basics: What It Is, and What It's For

Suspending students from school is a drastic measure that's sometimes necessary, but often applied inappropriately. When is it the wrong response, and when is it an essential tool for protecting teaching and learning?

In this article, I'll use the term “suspension” to refer to short-term out-of-school suspension, in which students remain enrolled in the school but are required to stay home for 1-10 days—and miss all extracurricular activities—as a disciplinary consequence.

Removals longer than 10 days may also be called suspension, e.g. for severe issues such as weapons or drugs. Long-term suspensions may extend to 45 days, a semester, or even a whole year. In this article, we'll focus on short-term suspensions of 1-10 days.

In-school suspension is also a common consequence, used instead of, or for less severe behaviors than, out-of-school suspension. Because many of the considerations are similar, I won't distinguish between OSS and ISS in the remainder of this article, nor will I discuss the unique features of ISS.

Suspension Creates Boundaries for Behavior

The primary function of out-of-school suspension is to create boundaries for student behavior—to draw bright lines around behavior that will not be tolerated, such as violence, harassment, and other extreme disruptions to learning.

When a student is suspended from school, the student, the student's family, other students, teachers, and the public receive the message that certain behaviors are not tolerated at school, and that to remain in school, students must keep these behaviors in check.

Crucially, suspension creates a sense of procedural safety—the understanding that, while we can't completely prevent behaviors such as assault or harassment, students and staff will be protected by policies that remove students who harm others from the learning environment. This creates a sense of predictability for everyone—leading to a feeling of safety for would-be victims, and dissuading would-be perpetrators from taking their chances.

Procedural safety is important because schools are compulsory environments; students cannot simply avoid peers with troubling behaviors as they might outside of school. Schools also also have rules that prevent natural consequences from operating as they do outside of school, where violence is likely to be met with retaliatory violence or law enforcement. In school, students are expected not to take revenge or call the police, so schools must ensure procedural safety.

It's of the utmost importance to the legitimacy of schools and school leaders that they respond effectively to violence and other serious misbehavior. When students misbehave with impunity, the school loses legitimacy, and bad behavior proliferates.

When students exhibit violent or other extremely disruptive behaviors and are allowed to remain in school, everyone receives the message that such behaviors are acceptable and must simply be tolerated by other students and staff, regardless of the negative impact on the learning community.

Any Student Can Be Suspended—Including Students Who Have IEPs & Receive Special Education Services

School administrators often get the message that they cannot suspend students with IEPs for any reason—but this is false.

In the US, special education law limits suspension to 10 total days in a school year for students with IEPs. After 10 days, the IEP team must hold a manifestation determination meeting to assess whether the behavior was a manifestation of the disability.

IDEA, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, protects students from being disciplined for their disabilities. For example, a student with autism who becomes overstimulated during a noisy activity needs to be supported in moving to a quieter environment, not punished for a largely involuntary reaction.

However, these protections are often misunderstood. An IEP does not give the student free rein to harm others without consequences. When a student with an IEP exhibits unacceptable behavior, there are essentially three possible causes:

- The behavior is a manifestation of the student's disability, and the IEP is appropriate, but was not implemented correctly by staff

- The behavior is a manifestation of the student's disability, but the IEP is not appropriate, and needs to be revised (which may or may not include a change of placement)

- The behavior is NOT a manifestation of the student's disability, and the student should receive consequences just as a student without an IEP would

Administrators may find themselves in a bind if they realize a student's placement is not appropriate, because other placements may not be available or may be expensive or difficult to access. However, suspension can serve as an important form of evidence about the appropriateness of a placement.

State laws vary, and this article is not intended to provide legal advice regarding any aspect of special education.

Yes, Suspension Reduces Repeated Misbehavior

Because a small number of students facing the greatest challenges may get suspended multiple times, opponents of suspension have contended that it doesn't work—in other words, that it doesn't prevent the behavior from reoccurring.

Or even more alarmingly, they contend that suspension actually worsens behavior and alienates students from school.

Despite a great deal of concern over these issues, there is no high-quality research—such as random-assignment studies—to support these claims. The evidence we do have indicates that removing suspension has disastrous unintended consequences. Discipline reform efforts have created natural experiments in a number of cities:

There are district-wide case studies that provide useful insight. Philadelphia rolled back their use of suspensions in 2012–13, and the findings from one academic review are concerning. Reading and math scores plummeted, truancy increased, and the occurrences of violent crime spiked. Ironically, students ended up spending more time suspended because they received fewer suspensions but for worse infractions, thereby garnering longer punishments. Similar results arose in New York and California.

Daniel Buck, Fordham Institue

In fact, while many students are suspended at least once in their K-12 career, longitudinal data shows that fully half are never suspended again. This suggests that suspension has a strong deterrent effect against repeated serious misbehavior.

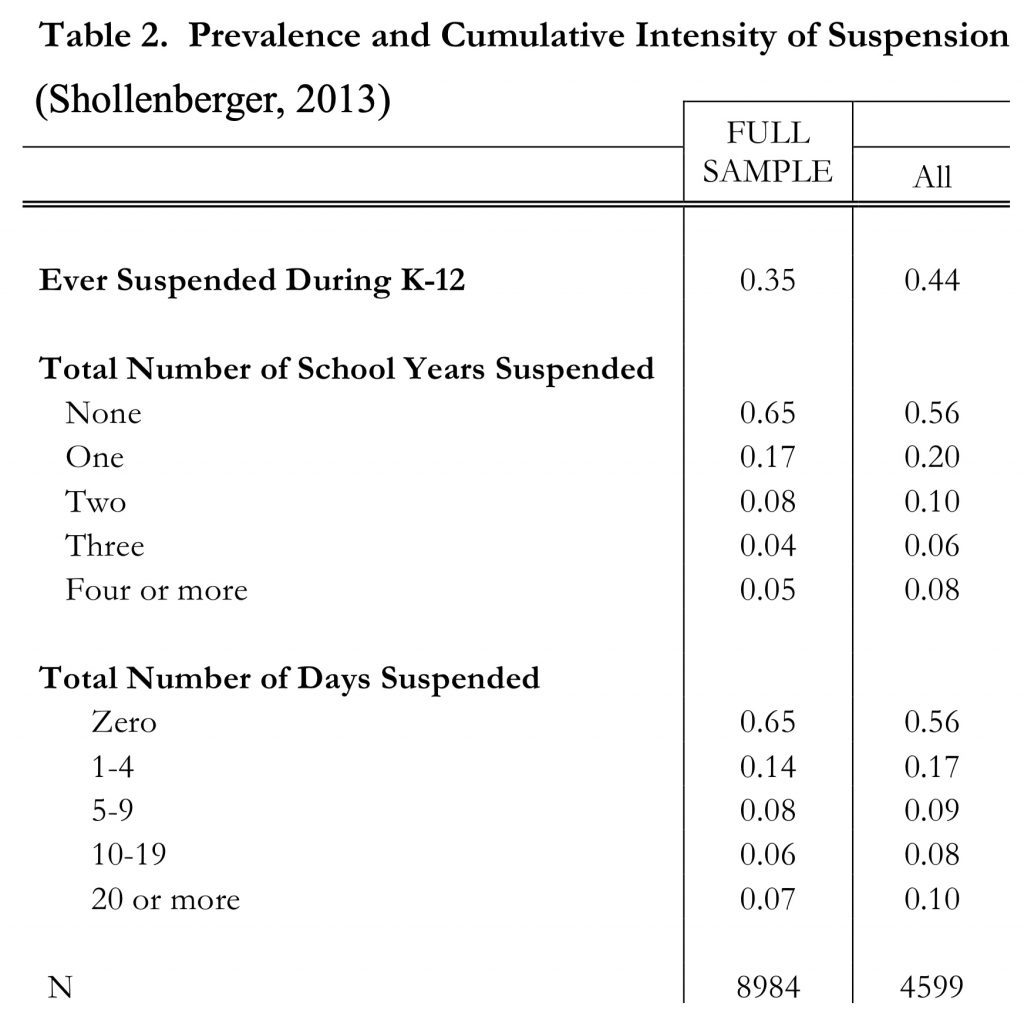

About 35% of all students are suspended at some point. Setting aside the deterrence effect of suspension on the 65% of students who are never suspended, there is strong evidence that suspension reduces recidivism.

Of the 35% of students who get suspended, 17% are suspended in one school year, 8% are suspended in two different years, and 4% in three different years. Only 5% of students are suspended in four or more different school years.

Similarly, we see a tapering-off effect in the total number of days suspended: 14% of students are suspended for 1-4 total days, 8% for 5-9 days, 6% for 10-19 days, and 7% for 20 or more total days across their K-12 careers.

The implications of this pattern are clear: each additional degree of suspension deters about half of students from further serious misbehavior. This is a robust and encouraging effect.

If suspension was not an effective deterrent to recidivism, we would not see such a dramatic drop in repeat suspensions.

(In contrast, criminal recidivism rates for youth hover around 80%, suggesting that the young people facing the greatest difficulties need far more than deterrence.)

Suspension Doesn't Really Help the Student, And Shouldn't Be Expected To

Suspension does not, however, teach appropriate replacement behaviors, build social skills, or address the many out-of-school factors that may be contributing to inappropriate behavior.

Critics of suspension often point to these limitations as evidence that suspension is futile or even harmful. Indeed, students who are suspended may or may not “learn their lesson” and change their behavior.

The power of suspension is in reinforcing boundaries for acceptable behavior in school.

When a student who has been suspended returns to school, they may still face challenging personal circumstances, struggle with behavior, and need to develop social skills, but at the very least they have not learned that they can misbehave with impunity.

In contrast, when students are not removed from class despite the most extreme behaviors, they develop a sense of impunity, schools become unsafe, anxiety rises, and staff turnover soon follows. News stories are replete with examples.

It's important to have modest and realistic expectations for what suspension can accomplish for the individual student. But it's also essential to examine the impact of suspension on the rest of the school community.

Suspension Protects the Learning Environment

Suspension primarily benefits everyone else—other students and staff who are, for a short time, able to work without the distraction of a student who has been disruptive or violent.

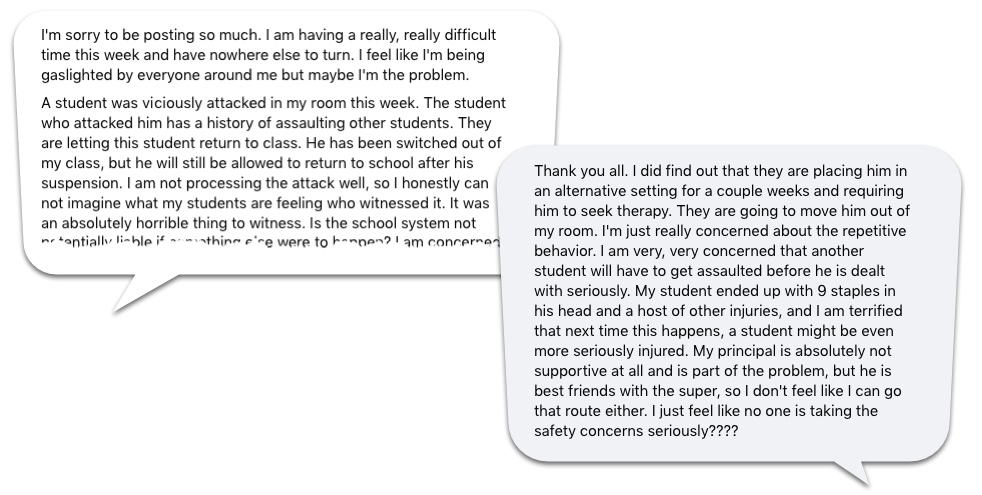

It is important not to understate the impact of misbehavior—especially violence—on other students and staff, who regularly report crippling anxiety after a violent attack on campus. A teacher recently shared her concerns on social media:

Thankfully, in this case, the student was placed in an alternative setting with a more appropriate level of services. Too often, though, students quickly return to the same classroom where they have assaulted their teachers or peers, and everyone is expected to return to business as usual.

Is Suspension An Inhumane Punishment?

In recent years, concerns about suspension have grown to the point that one could be forgiven for thinking it's a cruel and unusual punishment.

Certainly, students need to be in school in order to learn, and it's not fully possible to make up for the experience of being in school by sending work home for students to complete while suspended.

However, the limited evidence we have suggests that suspension has a neutral or even positive effect on academics.

Many observers note the strong correlation between suspension and poor academic outcomes, but this is largely a selection effect: the same stressors that contribute to poor behavior also contribute to learning difficulties. Simply eliminating suspension does not change these contributing factors.

To be sure, schools have a long and troubling history of problematic punishment and mistreatment of students, from the mass graves found around Canadian Indian residential schools to the paddling that still takes place in many rural schools in the US.

For most of human history, harsh punishments such as whipping have been common. We've seen a steady decline in these forms of punishment over time, and thankfully it is now widely (though not universally) agreed that corporal or physical punishment has no place in education.

But let's put suspension in perspective—is it actually a punishment?

Inherent to the idea of punishment is the element of suffering—some sort of intentionally adverse treatment that they experience as unpleasant or painful.

Do students actually suffer in any real way when they are suspended from school?

Given that students are already not in school most of the time, no. Let's look at the numbers.

Students Are Already Out of School Most of the Time

To be sure, many students have difficult home lives, and educators may feel a reluctance to force students to spend even more time at home. However, given the realities of the clock and calendar, students are only at school for about 16% of their lives. An extra few days at home makes no appreciable difference.

By law, the school year is typically about 1,000 instructional hours, or 5.5 hours a day for 180 days. Even if a student spends an additional hour before and after school riding the bus or participating in activities, bumping the total up to 7.5 hours a day, that's only 1,350 of the 8,760 hours of the a year.

Students already spend more than 84% of their time out of school:

- 16.5 hours a day

- Two full days a week (Saturday and Sunday)

- Two full months a year

- Holidays and staff development days

Unless we accept the bizarre proposition that Memorial Day, summer break, and weekends inflict suffering upon students, it is difficult to argue that suspension is a punishment in any meaningful sense.

If a student's home environment is truly unsafe, educators are mandatory reporters, so any such concerns should lead us to call Child Protective Services, not fret about suspension.

Reducing Out-of-School Suspensions

Suspension is a relatively drastic measure, and not one that should be used lightly or simply because a staff member is upset with a student.

Schools must follow clear, consistent policies for suspension, and strive to reduce inappropriate suspensions and bias to the greatest extent possible.

Let's look at a few opportunities.

We Can Easily Eliminate Illogical Suspensions

Some of the opposition to suspension stems from its inappropriate and illogical use.

Incredibly, a large number of schools continue to suspend students for being tardy, cutting class, or racking up unexcused absences, which is completely legal in 33 states:

Suspending students for missing class — whether it’s because they showed up late, cut midday or were absent from school entirely — is a controversial tactic. At least 11 states fully ban the practice, and six more prohibit out-of-school suspensions to some extent for attendance violations.

That leaves schools in much of the country, including Arizona, free to punish most students for missing learning time by forcing them to miss even more.

When the punishment is the same as the crime: Suspended for missing class—The Hechinger Report

Clearly, this is an illogical and counterproductive consequence that helps no one. Other students and staff do not benefit from an improved sense of safety and order, and certainly the suspended student does not benefit.

But ending inappropriate uses of suspension should not lead us to eliminate all suspensions, especially for the most extreme and harmful behaviors.

We Can Reduce Suspensions for Less Serious Behaviors, But It's Not Free or Easy

Evidence from recent efforts to reform school discipline suggests that suspensions for more subjective and less serious behaviors can be reduced without harming the learning environment.

But suspension has a built-in advantage that many schools will be reluctant to give up: it's free and easy to implement.

It costs nothing to suspend a student (except, perhaps, the loss of a few days of attendance-based funding), and it does not require any staff supervision. A suspended student is simply not our problem for a few days.

Alternatives like detention, saturday school, lunch detention, and in-school suspension, require staff supervision and can quickly run into the six figures per year.

However, these alternatives may be more appropriate for many common behaviors that are less serious, but still need to be addressed.

What Behaviors Should Lead To Suspension?

Students should be suspended for behaviors that pose a serious threat to safety and order, in accordance with district policy.

For behaviors that do not pose a serious threat to others or the learning environment, school-based consequences are more appropriate.

California passed a law in 2019 banning suspension for “willful defiance” for grades K-8, and many jurisdictions are attempting similar reforms. This particular category of misbehavior has attracted attention because it encompasses such a wide range of behaviors, and can lead to inconsistent application and a disproportionate impact on students of color.

“Defiance” is a nebulous term, and one that can obfuscate the source of a problem. Was the student completely to blame, or merely acting reasonably in response to a teacher with poor classroom management skills?

Clearly, other students do not benefit from improvements to the learning environment if a suspension is mainly due to a staff member having a bad day.

In contrast, suspending students for violence and other extreme behaviors has an immediate and dramatic impact on others.

Students see that unsafe behavior has consequences, and staff know they can trust school administrators to uphold the boundaries that protect their safety.

Ultimately, each district must develop its own discipline policy, and determine which specific behaviors justify out-of-school suspension.

At a minimum, though, students should almost always be suspended for acts of violence that result in injury, or for severe bullying, intimidation, or harassment of students or staff.

Addressing Racial Disproportionality

What about racial disproportionality in school discipline? Schools often examine their approaches to discipline in response to alarming degrees of disproportionality.

Addressing Racially Biased Policies

At one level, school policies themselves may be racially biased—for example, those focusing on hairstyles. Such policies lack any credible academic rationale, and frequently have the effect of targeting Black students.

Typically, these biased policies do not refer to race explicitly; in legal terms, they are “facially neutral” toward race in that they apply to everyone.

Clearly, though, a rule requiring short haircuts for boys will have a racially disproportionate impact on Black students, as in the widely reported case of a high school wrestler forced to cut his dreads or forfeit a match.

Such biased policies are fairly easy to identify, and they are growing increasingly rare as public pressure mounts to eliminate them.

A simple question is all it takes: Is this policy fair to everyone, or does it unfairly target some students?

Addressing Racial Bias in the Discipline Process

A second type of bias is more difficult to detect: bias in the application of discipline policy.

As the 2023 Department of Education guidance illustrates, this type of bias must be addressed by examining specific cases qualitatively, not merely looking at statistics.

Recent research suggests that racial bias on the part of principals is growing increasingly rare, though it certainly still exists (Eden, 2019).

A more persistent problem is the small number of teachers who send an unusually large number of students to the office.

Clearly, there are specific cases in which an individual educator's cultural competence results in disproportionality at the level of office referrals.

School administrators have the opportunity to disrupt this type of bias by both providing professional development on cultural competence, and by declining to issue consequences for spurious referrals.

New Federal Guidance

In May 2023, the US Department of Education an US Department of Justice jointly released new guidance for schools and districts, replacing much-criticized guidance from 2014.

This document contains numerous case studies of districts that were found to discipline students unfairly based on race.

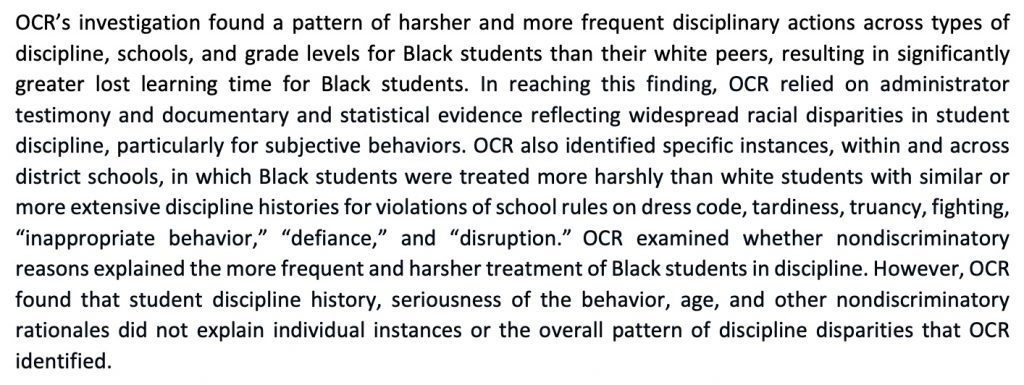

For example, the report details findings by the Office of Civil Rights in one high school district in California (p. 2):

It's important to note the degree of procedural unfairness in this case: students received different consequences for the same behaviors based on race.

To identify this pattern, OCR had to carefully examine the reasons behind the disproportionality in the district's discipline statistics, not just the raw data.

In the Department's earlier guidance, conveyed in the infamous 2014 “Dear Colleague” letter, schools were warned that disproportionality alone was evidence of discrimination.

However, disproportionality has two possible sources:

- Bias in the discipline process itself, as in the examples above

- Upstream inequalities in society, which have a multitude of downstream effects, including (but not limited to) school discipline

In a society as unequal as the United States, poverty is an obvious contributor to disproportionality. But there are other culprits, too, such as lead exposure (many of which track closely with poverty).

Clearly, school-level changes cannot address problems rooted in lead exposure or other upstream inequalities.

Schools Can't Offset Out-Of-School Contributors to Disproportionality

We can—and must—focus on the factors that take place in the school environment, but go no further.

We can address biased policies or the biased application of those policies, as well as the cultural competence of staff. However, such reforms will only partially address the disproportionality that appears in discipline statistics.

When schools attempt to offset out-of-school factors by adjusting their discipline practices, the result is essentially a suspension quota system that treats students differently based on race.

Such efforts are not progress. We cannot produce equity at the stroke of a pen by simply assigning arbitrary consequences in order to produce more palatable statistics.

Let's be clear: discipline must be based on the student's behavior, not the student's race.

Two students with similar behavior should receive similar consequences, regardless of race.

How should schools approach the question of consequences and administrative judgment?

Clear, Transparent Guidelines for Administrators

School discipline is an issue that invariably depends on sound professional judgment on the part of administrators.

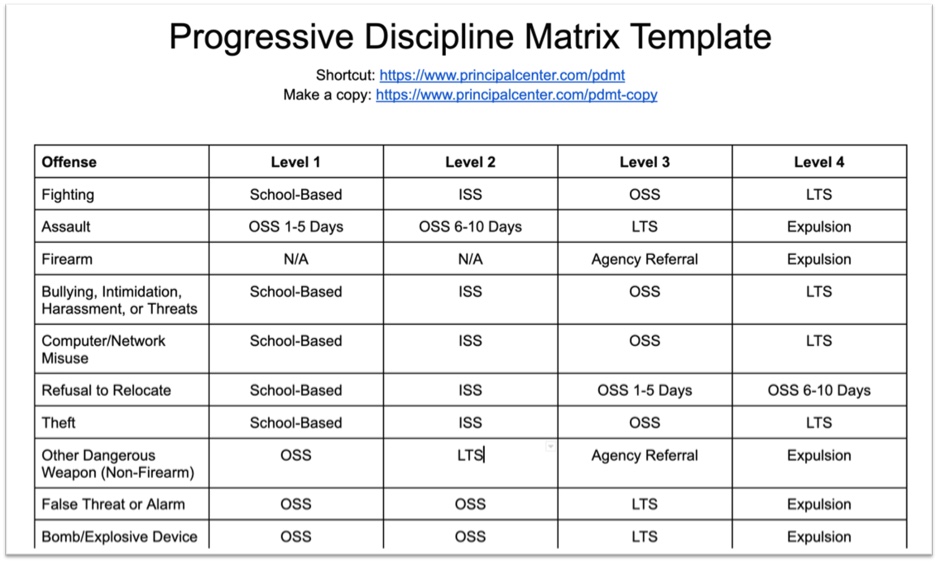

This judgment must be guided by clear policy—ideally in the form of a progressive discipline matrix.

A matrix of this type, shared with staff, students, and families, creates the necessary accountability for ensuring that administrators' decisions are fair and unbiased.

But school administrators also need discretion to adjust consequences based on the severity of the incident or a recurring pattern of behavior. In the example above, behaviors are divided into levels of severity, with accompanying consequences. Such guidelines allow administrators to exercise professional judgment while being held accountable for the fairness of their decisions.

Attempts to eliminate administrator judgment from the process entirely—by, say, banning suspension entirely on the one hand, or implementing zero-tolerance rules on the other—tends to result in poorer decisions.

Learn More About Progressive Discipline

To learn more about protecting your learning environment with effective progressive discipline systems, check out our free resources.

At The Principal Center, everything we offer on school discipline is free—we do not offer any paid programs or consulting on these topics.